Raoul Wallenberg Day in Sweden • New online exhibit focuses on young Holocaust survivors • Study finds PTSD effects may linger in body chemistry of next generation • Guest Post: Kinamedia Magnus Fiskesjö - Testimonials of China's Gulag for children • The Past is Present - Alexei Navalny reads Nathan Sharansky’s prison memoir in prison • Public seminar in Almedalen - Why is Sweden so quiet about Raoul Wallenberg? • Video Appeal for information about Raoul Wallenberg ready for launch • The 2023 Raoul Wallenberg Prize and Young Courage Award • Guest Post: Svenska Dagbladet Anders Gedin and Pontus Rudberg - Unreasonable Secrecy at the Swedish National Archives • Expert debate: Expressen and Dagens Nyheter - The decision to stamp the passports of German Jewish immigrants with the letter “J” • … and no, still no content restored on the Swedish government website …

RWI-70 5-2023

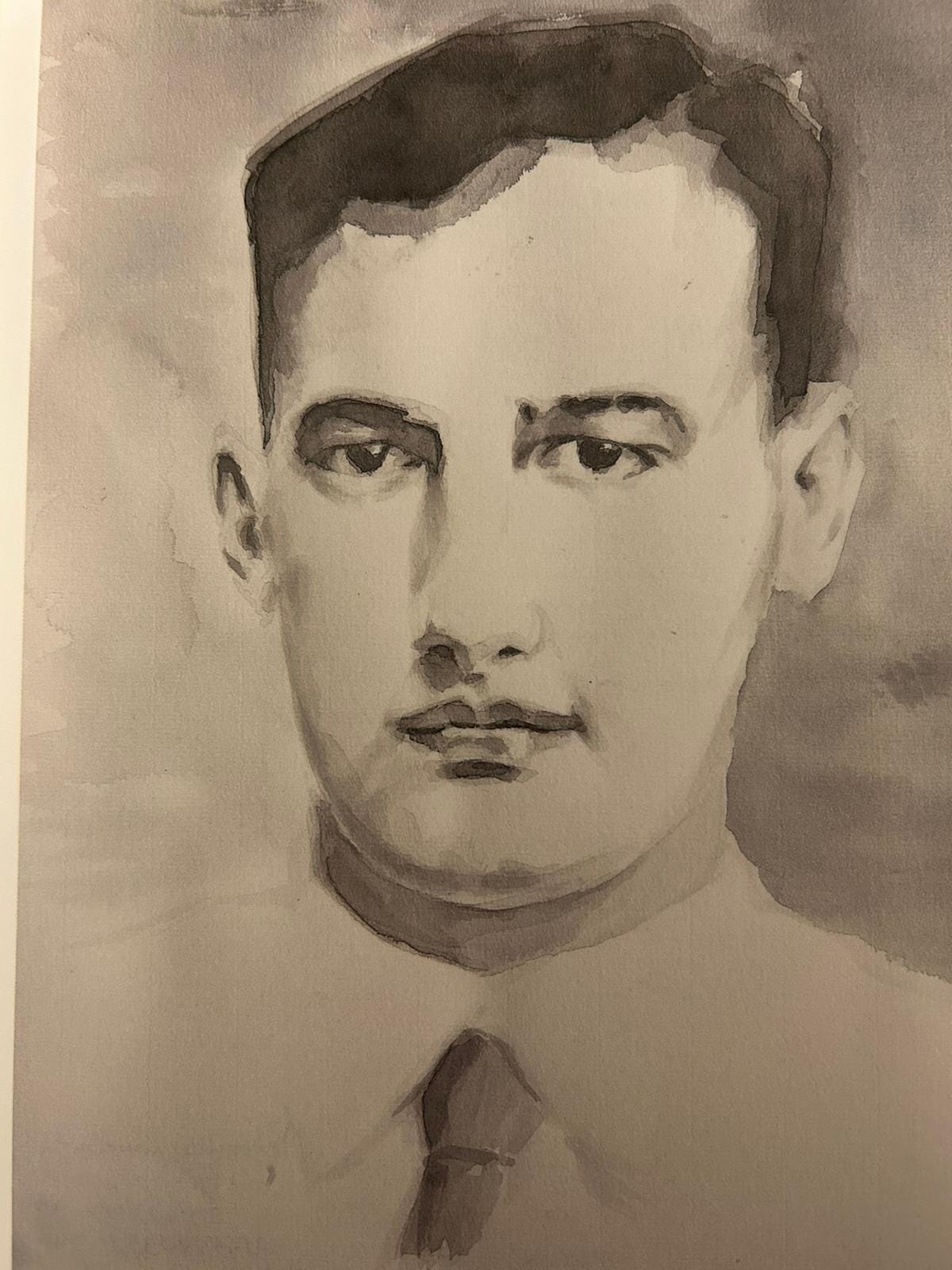

On August 27th Sweden celebrates Raoul Wallenberg - a day to remember his exceptional courage and activism, as well as the lasting effects and trauma of war.

This edition of our circular features several articles focused on the many different manifestations of trauma suffered by Holocaust survivors, including lasting transgenerational effects, such as PTSD. In his rescue work, Raoul Wallenberg focused especially on children. We see the devastating cost of war and repression for the future generations all over the world, in Ukraine, Syria, Yemen, Iran - and in China. So, I wanted to take a moment to highlight this very difficult but important subject with an article that appeared originally in Kinamedia last year, regarding the horrific present-day conditions in China’s Gulag for children. It’s a long article but well worth the time.

Returning to Sweden, I want to draw your attention to an interesting discussion that has erupted about excessive secrecy restrictions governing historical records (with important implications also for the Wallenberg case), plus a debate regarding the genesis of the special stamp “J” stamp placed in the passports of German Jewish immigrants to Sweden during WWII.

A quick update on the ongoing saga about the removed content regarding Raoul Wallenberg and other Holocaust related issues from the official Swedish government website. On August 3rd, I received a message from an official at the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, saying that the Ministry would be sending a formal response to our concerns in a week or two. So far, no message has arrived. No content has been restored and the website of the Swedish Holocaust Museum continues to show zero (“o”) entries for one of Sweden’s most honored citizens. Since this defies any rational explanation or further comment, I think we simply commence our own celebration and appreciation.

I will be back in a few weeks with an in-depth research update and the preparations for a new Raoul Wallenberg International Roundtable.

Susanne Berger

Coordinator, The RWI-70

Free online exhibit focuses on young Holocaust survivors

Andrew Palamarchuk

August 3, 2023

At age 11, Kitty Salsberg was orphaned and was thrust into a parenting role for her younger sister, Ilonka.

“I didn’t voluntarily take over that role, but she had made me take over the role,” Salsberg says of her sister. “She clung to me, and of course, I responded.”

The sisters, born in Hungary in the 1930s, lost their father in 1942 when he was taken for slave labor by the Nazis. Two years later, their mother was taken to a concentration camp and never returned.

“My father was probably exploded on the Ukrainian front as a slave laborer because they used to have the Jewish guys go out and look for the mines,” Salsberg said. “I endured the trauma of the loss of my parents. They were young and good people, and they did not deserve (that) kind of life or death and (that) kind of suffering. … They loved their children so much, and they had no idea when they got separated from us, if we will ever survive.”

The sisters would survive, but barely …

Read the full article here. Thank you to Celine Szoges Schwartz for forwarding it.

Study finds PTSD effects may linger in body chemistry of next generation

This report aired already seven years ago, but it remains, unfortunately, as current as ever as we face a whole new generation scarred by armed conflict and the trauma of war, the world over. Very much worth watching.

Guest Post

Testimonials of China's Gulag for children

This article appeared originally in Swedish by Kinamedia, on October 6, 2022

Magnus Fiskesjö

Two Uyghur children now living in Istanbul, Türkiye, are the only ones we know of who were released from the children's Gulag in China - the Chinese schools and orphanages where the Chinese regime locks up all the children whose parents have been arrested and thrown into indoctrination camps.

It is likely that there are at least several hundred thousand children who are currently separated from their families. The number of adults put in extrajudicial camps has been estimated at 1.8 million; Many of them have since been moved on to slave labour, or they have been sentenced to long prison terms. Their families are permanently broken up.

To these must be added all the children who are forced to go to Chinese boarding school even though parents or grandparents remain at home. The total number of children in compulsory care has been estimated at 900,000; I think it is quite possible that there are even more children confiscated by the Chinese state to be brought up in Chinese alone.

Until now, we have only had anecdotal knowledge of the conditions of all these children, but now we have two testimonies from children who suffered through the Chinese orphanages.

Lütfullah was four years old and his sister Aysu six years old, when they were taken from their parents Abdüllatif Kuçar and Meryem Aimati, during a visit to China. His father, Kuçar, was single-handedly returned to Türkiye because he had Turkish citizenship. The mother, Miriam, was forced to stay alone with the children, but was arrested late one night, while talking to her husband on the phone.

The children were taken the next day, and then held for 20 months at two separate schools, just outside the regional capital Urumqi, before they were allowed to leave China thanks to the father's insistence that the children were also Turkish citizens.

First of all, the children were not allowed to speak Uyghur, only Chinese. Aysu and Lütfullah had had time to learn to speak some Turkish, and it was also forbidden. The slightest communication in a language other than Chinese was punished – for example, by forcing children for long periods to crouch in a "motorcycle position" with their arms outstretched, as a kind of torture for children.

Nor was anyone allowed to say anything at all, without the permission of the guardians (staff), who also appointed one older child per room as a kind of assistant, who also often beat and harassed the other children. No one spoke to each other.

After 20 months, when they were driven to the father in a police car so he could fly with his children back to Türkiye, the children were emaciated, hunched and silent. They had forgotten all Uyghur and Turkish and could not talk to their parents. They couldn't say a single word—probably a result of fear of punishment. It took months before they regained their language skills and dared to speak as usual.

These observations are consistent with the many anecdotal reports that have come to light in the past, such as the much-publicized mobile video circulating in 2020, in which a Uyghur father in Istanbul suddenly saw a video of his now Chinese-speaking son on social media – from inside a Chinese orphanage. We also know that all communication in the mother tongue is severely punished even in the adult penal camps.

The children's entire existence was heavily regimented, and punishments were constantly meted out by their Chinese guardians. The children were beaten for the slightest offense, or they were trapped in dark rooms. As a result, Aysu and Lütfullah did not even dare to go from one room to the next in their apartment in Istanbul without first asking permission.

The deep fearfulness instilled into Aysu and Lütfullah frightened the father and other family members when they first saw them again. They had become completely different: "They were like the living dead," their new stepmother told American journalist Emily Feng, of Han Chinese ethnic origin, who has produced a long list of high-quality reports on the atrocities in the Uyghur region — known in China since imperial times as Xinjiang ("the new frontier").

The hundreds of thousands of children forcibly taken into custody by China probably live their days much like Aysu and Lütfullah: cowed, half-starved, and in constant fear.

This is again consistent with what we know about the atmosphere inside the penal camps for the adults (including the chronic famine) and, for that matter, in society as a whole, where everyone now lives in fear of being sent to the same camp – and having their children being taken away, and never seeing them again.

What about Mamma Meryem? She had meanwhile been sentenced to 20 years in prison — a typical, apparently arbitrary sentence that seems to be imposed on many middle-aged or sick people who are not fit for slave labor: Actually, a kind of death penalty where you are not executed directly, but tormented to death instead.

But somehow, the Chinese authorities had also agreed that Meryem would see her husband and children one last time before leaving China. She was driven from prison to a hospital where the family was given fifteen minutes.

Her father, Abdüllatif, broke down when he saw how emaciated she was, lying in a hospital bed. The arms had black marks from all the handcuffs. It was forbidden to touch her, but he couldn't help it, and lifted her up. He realized that she couldn't even stand on her own, that she had become skin and bones.

Time was up; the three left the hospital and flew to Istanbul.

China's campaign is a kind of genocidal psychosis, a century trauma with indescribably cruel consequences that may take generations to treat and cure.

But the Chinese state's actions against children have a concrete purpose: to destroy the next generation of the Uyghur people, so that there will be no future generations.

That is why the Chinese government wants to take away the children's language and cultural identity, so that they become Chinese, and no longer Uyghurs. This is an important part of the state genocide program against the Uyghurs, who number more than twelve million people, which has been ongoing since 2017 and for which Party chief Xi Jinping is personally responsible.

All of these measures - taken together, the largest attack on an ethnic-religious minority since the Holocaust - are clearly illegal, not least under UN Genocide Convention Article 2(e), which identifies the confiscation of children from one group to another, as one of the five main pieces of evidence of genocide.

Then there is the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which China has also ratified but is now just as blatantly violating: for example, paragraphs 9.1 (prohibition of separating families) and 16.1 (arbitrary attack on a child's home).

The Chinese regime would, of course, claim that their extrajudicial collective punishment of twelve million Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other ethnic groups is "necessary," that boarding schools are the best possible option for all the children, and so on.

But the central point here is precisely the lack of judicial review: China punishes and forcibly converts millions of innocent people against their will, without trial or proof that any of them committed any crime whatsoever – and even that could not of course justify the collective punishment that we see in China's general attack on the Uyghur language and culture. the bulldozing of monuments, mosques, places of pilgrimage and other important cultural heritage.

This is a racially based, state-orchestrated campaign that violates international law, and for which those responsible should be tried in the international courts in The Hague, or in a special Xinjiang tribunal.

Sometimes China's "friends" in the West try to divert attention away from children in China by changing the subject to US President Donald Trump's move last year to break up migrant families and take their children, at the Mexican border.

China's defenders want Trump and China to be equally bad actors. But there are big differences. The American policy was not about forced conversion to a new identity. The extrajudicial abduction of the children was simply intended to discourage other migrants from coming to the United States and seeking asylum.

But Trump's project was soon exposed by the American media, it became a major scandal, and everything was stopped. At its peak, around 5,000 children were affected – several hundred Latin American children have apparently still not been reunited with their families. The psychological consequences have been studied and show that separation creates deep wounds that stunt the children's development.

It suggests the dark hell in which hundreds of thousands of Uyghur children live. In China, it involves at least 100 times more children, a low estimate. In China, there are also no independent media outlets that can report on them; or courts, where parents or human rights organizations can sue the Chinese state, as in the United States.

And in China, the aim is obviously to speed up the conscious process of eliminating an entire people and its language and culture, so that the indigenous population of the Xinjiang Chinese colony (Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other ethnic minorities) can be completely replaced by Chinese colonists — the new master people.

Relevant comparisons in modern times with this human rights disaster would be with Spanish fascism and the Latin American fascist regimes, which also systematically kidnapped children in order to "convert" them to a fascist ethos of life!

Even more directly comparable would be the forced schooling of Sami children in Sweden in the past, and the forced care of Indian children in the United States and Canada, all of whom were forced – often by the Church – to abandon their mother tongue and their native religion.

Or Vladimir Putin's new, ongoing program to bring Ukrainian children to Russia and retrain them as Russians, that is, also a genocide according to the UN's "Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Genocide)," from 1948.

Magnus Fiskesjö - Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, Cornell University

FURTHER READING AND LISTENING:

"The Black Gate: An Uyghur Family's Story", Part 1 and Part 2 – National Public Radio, by Emily Feng (Sep 25, 2022)

"Uyghur Kids Recall Physical and Mental Torment at Chinese Boarding Schools in Xinjiang" – National Public Radio, by Emily Feng and Abduweli Ayup (Feb 3, 2022)

"Uyghur Human Rights Project Documents Continuing Assimilationist Policy Targeting Uyghur Children" – Uyghur Human Rights Project (Jan 2022)

"Orphaned by the State: How Xinjiang's Gulag Tears Families Apart" – The Economist (Oct 17, 2020)

"Uyghur Bibliography" – Uyghur Human Rights Project (updated continuously)

The Past is Present - Alexei Navalny reads Nathan Sharansky’s prison memoir in prison

Earlier this month, Alexeii Navalny began his much-discussed essay, “My Fear and Loathing”, about the root causes of the failure of creating a stable system of democracy in Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union by commenting on his reading the memoir “Fear no Evil” (1988) of Soviet dissident Nathan Sharansky in his prison cell.

I am sitting in my SHIZO and reading a book by Natan Sharansky, Fear No Evil (I recommend it). Sharansky was jailed in the USSR for nine years, and in 1986 he was exchanged. He went to Israel, created a party, achieved great success. In general, he's a cool guy. By the way, he spent 400 days in punishment cells and SHIZO. I really can't imagine how he survived.

So, Sharansky describes the arrest and the investigation. 1977. I was one year old at the time. The book was published in the USSR in 1991. I was 15 years old at the time. Now I am 47, and while reading his book, I sometimes shake my head to get rid of the feeling that I am reading my personal file. For example, the SHIZO/PKT building — is a separate barrack behind the barbed wire. The maximum term in the SHIZO is 15 days. I was not surprised when after several «15 days» in a row I was transferred as a persistent offender to a PKT for six months. It was exactly the same.

In the introduction (I remind you, the year is 1991), Sharansky writes that it is in prisons that the virus of free-thinking persists, and he hopes that the KGB will not find “an antidote to this virus.” Sharansky was wrong. The antidote was found. The antidote that now, in 2023, seems to have more political prisoners in Russia than in the Brezhnev-Andropov times. What has the KGB got to do with it? There was no creeping or overt coup in our country led by people from the special services. They did not come to power by pushing the democrat reformers out of power. They did it themselves. They called them themselves. They invited them themselves. They taught them how to fake elections. How to steal property from entire industries. How to lie to the media. How to change laws to suit themselves. How to suppress opposition by force. Even how to organize idiotic, stupid, talentless wars.

…..

Only when the vast majority of the Russian opposition consists of those who under no circumstances accept fake elections, improper judicial proceedings, and corruption, then we will be able to make the right use of the chance that will surely come again. So that no one in 2055 will be reading Sharansky's book in the SHIZO, thinking: Wow, it's just like me.

There has been a strong reaction to Navalny’s critique of how democratic reform was squandered during the 1990s. Several people questioned whether he could have authored such a detailed manifesto in prison. Russia’s opposition is severely fractured and Navalny remains a highly controversial figure. At the same time, there is a virtually unanimous condemnation of the cruel conditions of his imprisonment. Meduza collected the different views and comments which you can read here.

Public Seminar in Almedalen - Why is Sweden so quiet about Raoul Wallenberg?

June 28, 2023 Organizer - Inblick

Raoul Wallenberg is an honorary citizen of the USA, Canada, Australia and Israel, he has had monuments, streets, schools, squares and buildings named after him around the world, but in Sweden the Swedish diplomat has not received as much attention. Why?

Background

At the end of World War II, Raoul Wallenberg was appointed as a Swedish diplomat and sent out by the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs on a humanitarian mission to save the Jews of Budapest from the Holocaust. The doctoral thesis of Swedish historian Paul Levine describes how Foreign Ministry bureaucrats went from indifference to activism against Hitler's antisemitic persecutions at the end of World War II. The majority of the 8,000 Danish Jews were rescued in the fall of 1943, a successful operation in which Sweden had an important role; and in the following year, the Swedish houses and the Swedish protective passports became the salvation for tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews in Budapest. Why are the rescue efforts of Raoul Wallenberg and other Swedish diplomats not highlighted more clearly when Sweden says it wants to be at the forefront of preserving the memory of the Holocaust?

In Swedish and English

Participants

Magnus Oscarsson, Member of Parliament, Riksdagen (KD)

Max Federmann, operations manager, Keren Kajemet

Susanne Berger, Historian, The Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative (RWI-70)

Peter Axelsson, analyst focused on Eastern Europe

Ruben Agnarsson, Moderator, Inblick

Video appeal for information about Raoul Wallenberg almost ready to launch

There is exciting news about the planned international video appeal for information about Raoul Wallenberg’s mission in Hungary and his subsequent fate in Russia: The video is almost complete and will be ready for launch shortly. Tel Aviv University (Dr. Ronit Kampf, PhD; Director, department course: Human Behavior, Digital Behavior and what Lies between Them) and longtime Wallenberg activist Max Grunberg played a crucial role in realizing this project, as did Tel Aviv University student Liana Baransky who handled the technical and creative design of the video. Watch out for the official launch in the coming weeks!

The 2023 Raoul Wallenberg Prize and Young Courage Award

From the Raoul Wallenberg Academy website (translated from the Swedish):

Every year, on August 27th, the Raoul Wallenberg Academy in Stockholm awards the Raoul Wallenberg Prize. The award goes to a person who works in Sweden in the spirit of Raoul Wallenberg, primarily through educational initiatives aimed at children and young people with the aim of countering racism, discrimination and intolerance and for the equality of all people. Raoul Wallenberg prize winners are role models – individuals that young people can admire and look up to.

In addition to the Raoul Wallenberg Prize, the Young Courage Award will also be presented. It is an international youth award in cooperation with the Swedish Institute (Svenska Institutet, SI) and the Swedish embassies in France, Spain, Serbia and Hungary, and is awarded to young people who have shown great physical and moral courage.

The award ceremony is broadcast live on our YouTube channel and starts at 15.00 Swedish time on Sunday. You can find the broadcast here.

Guest Post

In a recent commentary article published in Svenska Dagbladet, Swedish Professor of Art History Anders Gedin and Associate Professor of History Pontus Rudberg address the problem of excessive secrecy restrictions in historical research. A problem that is not limited to Sweden but also very much a topic of discussion throughout Europe and especially also in the U.S.

August 21, 2023

Unreasonable Secrecy at the Swedish National Archives

The Swedish National Archives applies secrecy restrictions unnecessarily strictly and unpredictably, which hurts both research and the citizens’ right to information.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the archives of authoritarian regimes were opened: the Stasi archives were made accessible to the public, the archives of the Czechoslovak Communist Security Police were published online, and the Polish Institute of National Remembrance opened its doors to researchers.

During this time, it became evident how colleagues, teachers, friends, and family members had been spying on behalf of the state. This was a painful yet necessary process because "how information is created, managed, and preserved is important on various levels and ultimately a matter of democracy," as stated by the National Archives in a response to the 2019 archive investigation report. However, officials at the National Archives apply secrecy unnecessarily rigorously and unpredictably, which damages both research and citizens' right to information, primarily concerning the historical archives of the Security Police.

According to a main rule, documents in the National Archives relating to Swedes should be released after seventy years. But there are additions that render the rules practically ineffective. The National Archives has to apply a reverse harm test, meaning that they should only release information that cannot lead to harm. Making these assessments of potential consequence is nearly impossible. Furthermore, "some are classified due to considerations of personal privacy or national security, for example." Rules and concepts like "harm," "privacy," and "security" are also difficult to handle, making it easier for the National Archives to classify documents as secret if they are even slightly uncertain. Here are three examples of the problematic application of secrecy regulations.

One of the signatories, Andreas Gedin, requested his grandparents' file in the of spring 2020. It contains information that his grandmother, Lena Gedin, had been visited by the press attaché at the Soviet Embassy in 1951 (a known spy), and that her husband, Georg Israel, had been in contact with the trade attaché at the same embassy. The explanations for this are simple: Lena Gedin was a literary agent and the press attaché was also a cultural attaché. Georg Israel traded metals, and the Soviet Union was a trading partner. The information is demonstrably harmless. But when Andreas Gedin requested the documents again in the fall of 2020, they were deemed classified as secret, referring to the so-called Secrecy Act (2009:400), to be released again in the fall of 2022. However, when they were both requested in March and July 2023, they were once again considered classified as secret. The assessments are inconsistent and unreasonable.

The cover of the Israel-Gedin couple's file is partially masked. When it was requested for the third time, some notes were revealed; the seventy-year limit had passed for some dated series of numbers and letters. These are references to other files, but the National Archives does not know which ones. They are either classified or information is released even when its meaning is unknown. In this case, the reverse harm test does not apply.

Pontus Rudberg, the other signatory, has requested the personal file of war criminal Walter Schellenberg from the archive of the Security Police. Schellenberg was a close associate of Heinrich Himmler, including as the head of the SS Sicherheitsdienst or SD (security service) and involved in planning the mass executions of the so-called Einsatzgruppen during the Holocaust.

It is evident to anyone knowledgeable about the facts that the information in the documents can be disclosed without any individual risking harm or danger. Schellenberg has been dead for seventy years, and his widow and daughter have passed away. All investigators and sources of information named in the file are deceased. The statute of limitations for all the crimes mentioned in the investigation has long since expired. Intelligence methods are well-known from before, and the information cannot risk harming the police or intelligence service today.

In the case of Schellenberg's personal file, the National Archives rejected the request, citing "secrecy under the Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act for the protection of individuals involved in activities aimed at preventing or investigating crimes."

The National Archives' decision can be appealed to the Court of Appeals. However, it is in the same position as the National Archives' officials; it is easier to deny than to approve requests, as the complainant does not know the contents of the documents and avoids challenging the National Archives' assessments. When Pontus Rudberg appealed, the Court of Appeals upheld the National Archives' stance. They referred to the provisions of the so-called Secrecy Act (2009:400), stating that information that could harm individuals or the work of the Security Police can be classified. However, strangely enough, the Court of Appeals made its decision without requesting the relevant documents and verifying the National Archives' justification.

During the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust in January 2000, Sweden and the other participating countries committed to "take all necessary measures to facilitate the opening of archives to ensure that documents related to the Holocaust are made available to researchers." Neither the National Archives nor the courts live up to this commitment, despite the existence of a specific provision in the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) law that enables the accessibility of such documents.

The National Archives' handling of secrecy creates an uncertain situation that contradicts the purposes of the regulations. Any potential "harm" should be balanced against a reasonable public interest and the needs of academic research. The current situation contradicts the idea of an open society and the spirit of the law, and the National Archives' handling of secrecy should be examined and revised.

Sweden’s wartime role in stamping the passports of Jewish immigrants with the letter “J”

Kulturdebatt August 16, 2023

Writing in a commentary article in Dagens Nyheter, Ola Larsmo ignores facts about Sweden and the J-stamp, claims historian Pontus Rudberg. He has reviewed previous research and archives showing that Sweden wanted to distinguish Jews from other German citizens.

Over the summer, Pontus Rudberg has been involved in another interesting historical discussion that has erupted in Sweden. It centers around the genesis of the decision to stamp the passports of German Jewish immigrants to Sweden with the letter “J”. This past June, the author and publicist Ola Larsmo argued that there was no evidence for such a policy. Professor Rudberg, an expert on Jewish history in Sweden, has researched the issue in depth and shows that it was indeed the Swedish government that moved to institute and authorize the special markings. You can find Ola Larsmo’s original two articles in Dagens Nyheter (unfortunately behind a paywall). Pontus Rudberg responded each time in Expressen.