An Appreciation

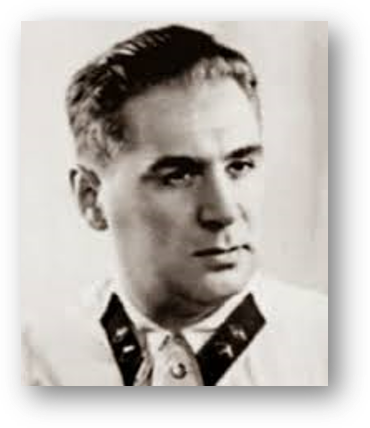

Dr. Vadim J. Birstein 1944 - 2023

For those of you who can’t be at the Plaza Jewish Community Chapel for the memorial service for Vadim on July 2nd at 3:00 pm Eastern Daylight Time (UTC-4), please note that the service will be Live Streamed. The link for the Live Stream is on Vadim’s Obituary page on the Plaza Jewish website, where there is also a registry that you can sign. A recording will also be made that will be made available on the internet.

https://www.plazajewishcommunitychapel.org/funerals-details/?fID=68

Vadim J. Birstein, New York Times obituary

https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/nytimes/name/vadim-birstein-obituary?id=52366622

Please see also Vladimir Abarinov’s tribute in Russian on the website of Radio Free Europe.

July 2, 2023

To say that Vadim was a multi-faceted man would be an understatement. I can already hear Vadim growl in my ear – “So what? What are you trying to say?”

Ok, just wait a minute, I am getting there …

I worked closely with Vadim for over twenty years – we had intense discussions, some arguments, and also many fun moments. We both loved the thrill of research and marching together into battle. He was formal, traditional and brilliant. He was also very private and intense. He was a stickler for precision to the point you just wanted to scream. He could be stubborn and irascible. But what many people may not realize is that Vadim was also shy and very sensitive, with a deep appreciation of the vagaries and fragility of life.

When I first learned that Vadim had left us, I felt like somebody had punched me in the stomach. All the air left my body. After the first shock wore off, a thousand different thoughts started racing through my mind. I tried to recall our last communications. Vadim did not want to talk about his illness. I respected his wish and simply kept him updated on our latest correspondence and ongoing research. We had developed an easy shorthand, sending each other news, often without comment. But his complete silence signaled that something very serious was amiss.

It is very strange what comes to your mind when you learn of a friend’s sudden death. I realize that there is so much I did not know about Vadim – our conversations were usually mostly focused on our work. I picked up snippets here and there about his life in Russia, his prominent and much-loved family, his stellar career as a biologist and molecular geneticist, his work as a human rights defender, especially with the legendary Russian human rights organization Memorial (founded by Andrei Sakharov and Sergei Kovalev). I knew he had come to the US in 1991, had fallen in love and settled into a very happy marriage. He leaves behind a daughter, Arisha, whom he fretted about like a mother hen and whom he simply adored.

Vadim did not speak much about himself – such conversations came about more or less accidentally. Like when we talked about a new Russian movie that premiered some years ago. He mentioned almost in passing that the stark setting reminded him of the remote region of the Kola Peninsula in the extreme north-east of Russia, where he had spent three difficult years in self-imposed exile in the late 1980s.

He had decided to leave Moscow when the KGB pressured him over his contacts with several dissidents. Once, when we discussed the interrogations of prisoners in the Soviet system, including Raoul Wallenberg, he relayed from his own experiences how exhausting and dispiriting these interrogations were, with KGB officers asking the same questions over and over and over again, with no sleep, no breaks and barely any food.

Vadim Jacobovich Birstein was born in 1944 into a prominent family of Russia’s Jewish intelligentsia.

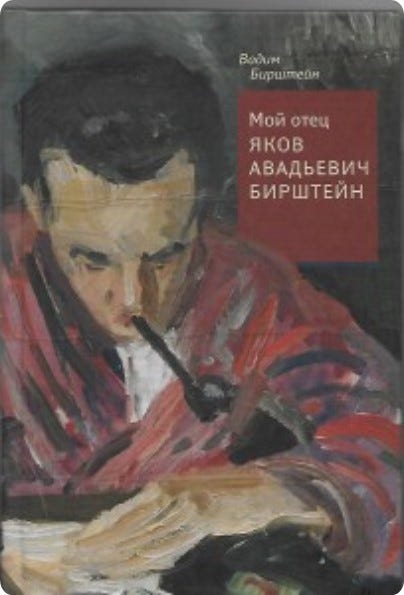

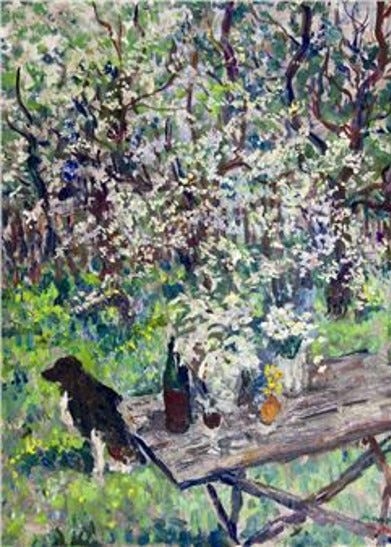

His father Yakov (Jacob) was a respected and celebrated university lecturer, a zoologist, oceanographer and evolutionist. (Talk about multifaceted!) His uncle Max was a talented artist and painter, his cousin Tatiana Maksimovna a world-renowned chemist. I love the opening pages of Vadim’s book about his father, where he describes waking up in the communal apartment in Moscow to see Jacob Birstein at his desk, writing lectures or compiling research notes, while his mother prepared breakfast. Meanwhile, in another corner of the room his uncle Max would put up his easel and feed the cats.

I have often thought about how the formative years of Vadim’s life were marked by the aftermath of a horrible war that cost 20 million Russians their lives, and the ever-present fear and repression of the Stalinist era. Intellectual pursuits and academic studies created a path forward for a young, clearly brilliant student from a Jewish background. Educated at Moscow State University, he received his Candidate of Sciences Degree in 1971, and Doctor of Sciences, in 1988. Until the end of 1998, he was a Leading (Senior) Research Scientist at the Koltsov Institute of Developmental Biology, Russian Academy of Sciences.

From 1993-96, Vadim was an Adjunct Professor of Biology at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. As you know, Vadim was one of the world’s leading authorities on sturgeons.

From 1995 – 1998 he served as the Director of Scientific Programs with The Sturgeon Society, Inc., of New York. Together with Dr. Rob DeSalle he elaborated a method of caviar identification via DNA analysis which was patented in the United States and Europe. Almost incredibly, until then caviar experts had relied mainly on the appearance and smell of the roe. Vadim also made important contributions to conservation. As Chairman of the Sturgeon Specialist Group of IUCN (World Conservation Union) he worked closely with TRAFFIC Europe, the German Ministry for the Environment, the World Bank, the WWF and CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) legal staff to promote legislation to ban the importation of the caviar of endangered sturgeon species into the United States.

Vadim had a highly curious and prolific mind, evidenced in the almost 200 scientific papers and books he published over his long career. Their diverse subjects ranged from chromosome mutations in sturgeons, the scientific study of old easel and wall paintings (Technology, Study and Conservation of Paintings and Murals), his research of Soviet counterintelligence history (including the highly charged espionage cases of Alger Hiss, Whittaker Chambers, and the poisoning of the former FSB officer Alexander Litvinenko) to a widely distributed report on torture in the Russian prison system.

This leads me to another aspect of Vadim’s work that is sometimes overlooked – the fact that in addition to his scientific work Vadim was a long-time dissident and human rights defender. In the 1970s-80s, he was an individual Amnesty International member in Moscow. Since 1989 he worked as a researcher for Memorial. In 1990, he participated in the visit of Russian and Polish historians to the Katyn forest, where in 1940 the NKVD executed thousands of Polish officers. Incidentally, Vadim visited one of the key-witnesses of the Katyn massacre, Boris Menshagin, the mayor of Smolensk, several times during the last years of his life which he was forced to spend in a squalid invalid home in Russia’s Arctic region. Menshagin had steadfastly refused to confirm the Soviet version of the executions and had spent the significant part of a 25-years sentence in strict isolation in Vladimir Prison - one of the Soviet Union’s toughest punishment prisons, located about 160 km north-east of Moscow.

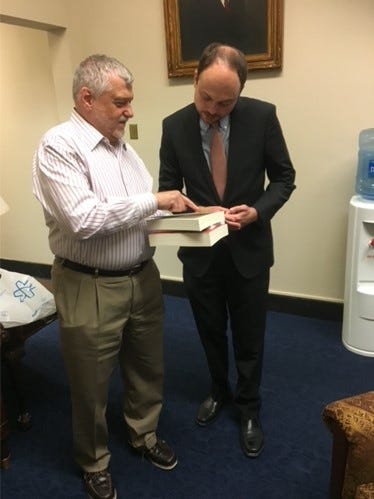

Vadim kept up his human rights advocacy after he arrived in the US – here he is a few years ago with Russian opposition politician Vladimir Kara-Murza when he gave one of his official testimonies in the U.S. Congress (regarding the adoption of the U.S. Global Magnitsky Act.)

Vadim brought the rigor of his scientific training in the natural sciences to his work as a historian. Actually, we would have long and sometimes heated discussions about this. The study of history, too, bases itself on precise sources and facts, but it also deals with many intangibles - hidden motivations and emotions, personal memories, etc. I would argue that scientists are also investigators – and as such, when faced with incomplete information, they must contemplate and test various reasonable scenarios and hypotheses. Vadim would have none of it, refusing for the most part point blank to consider any ideas for which he had no clear evidence. As he would say, “I cannot speculate about what I cannot see.” In these discussions, Vadim could be gruff and, frankly, very tough. But he would also be willing – after a lengthy period of silence – to concede a point and quietly make adjustments to our joint texts.

Surprisingly, we found our way past these storms and simply agreed to disagree – even on the most fundamental questions in the Wallenberg case. It is what enabled us to work together for so long. As many of you probably know, Vadim was not overgenerous with praise but when it came, it meant even more because you knew it was truly genuine. Vadim was very generous in other ways – he always made sure to answer other researchers’ queries and would share liberally from his great reservoir of knowledge, provided he felt that the person asking the question was serious and appreciated Vadim’s penchant for accuracy and details.

He remained keenly interested in life and events in Russia, staying in constant contact via phone and the internet. (Can you imagine what he would have made of the rather astounding events of the last few days?!) Unable to conduct research in Russian archives, he would nevertheless painstakingly collect all types of information, documents and official papers from his vast network of contacts. His first book on the history and perversion of Soviet science was truly remarkable.

His next book, on the history of the Soviet military counterintelligence organization SMERSH was a sensation. It was named the St. Ermin’s Intelligence Book of the Year in 2012, in the UK, and was translated into Polish, Estonian, Lithuanian and Russian. Undoubtedly, both publications will remain standard works on their subjects for decades to come.

Incidentally, the famous propaganda poster from 1941 you see on the cover of SMERSH – “Do not gossip!” – was created by Vadim’s aunt, Nina Vatolina, wife of his uncle Max.

Vadim’s contributions to the Wallenberg investigation are equally remarkable – spanning thirty years and, until his death, showing no signs of stopping. Since Raoul Wallenberg’s disappearance in Hungary in January 1945, his family - his parents, Maj and Fredrik von Dardel, along with his siblings Guy von Dardel and Nina Lagergren - fought an unrelenting battle to rescue him or to learn the truth about his fate. We all know that historical research is a relay race and a group effort. Still, Vadim’s achievements remain truly exceptional, providing a whole new understanding of the structure and function of the Soviet prison system, and, with it, the official handling of the Wallenberg case.

In 1990, Guy von Dardel used the opportunity of the collapse of the Soviet Union to create the first International Commission investigating his brother’s fate in Russia. The Commission worked closely with international researchers, as well as noted historians from Memorial, such as Arseny Roginsky and Dr. Nikita Petrov, and - of course - also Vadim. Vadim greatly respected Guy as a fellow scientist and for his unfailing loyalty to his brother. Dr. von Dardel’s research team was the first ever – international or Russian – to be permitted to examine the prisoner card catalogue at the aforementioned Vladimir Prison, one of Russia’s most notorious isolator prisons.

In April 1991, Vadim and Arseny Roginsky, a co-founder of Memorial, set to work in the Kremlin’s Special Archive which was highly secret at the time (now the Russian State Military Archive, RGVA). There they discovered the first ever proof that Raoul Wallenberg had indeed been imprisoned in the Soviet Union. Almost immediately, the KGB moved to close down access to the records. Swedish officials were well aware of this fact but did not formally protest the decision. Vadim next worked to identify and interview some of Raoul Wallenberg’s chief interrogators. He was also among the first researchers to publish articles in the Russian press about the investigation.

Vadim felt very strongly that only a truly independent, international inquiry could yield progress in the Wallenberg case. That, unfortunately, was never realized. Russian officials quickly made it clear that they did not want true experts like Vadim in the official Swedish-Russian Working Group that succeeded Guy von Dardel’s initial Commission. The Swedish government eventually acceded to the demands.

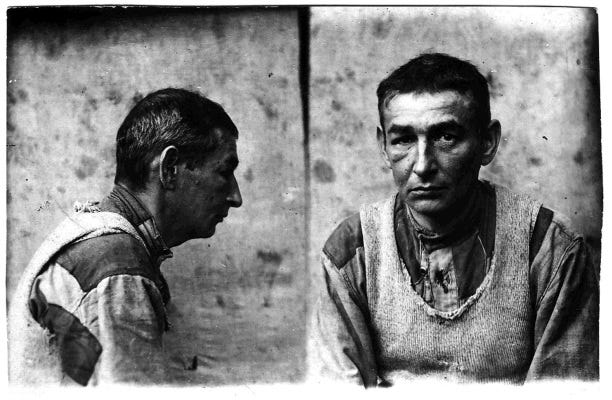

Why did Vadim care so much about Raoul Wallenberg and other political prisoners in the Soviet Union? This is why: You see here a young American citizen, Isaiah Oggins, imprisoned in Moscow from 1939 until 1947. You could easily be looking at Raoul Wallenberg. This is what Oggins looked like at the beginning of his sentence.

This is what he looked like eight years later, shortly before his death.

Vadim saw a lot of things very clearly – and much earlier than many others. He recognized the dangers of Vladimir Putin’s rise much faster than many other Western experts and commentators who would regularly downplay both his Chekist background and his strong arm tactics. Vadim picked up on the very early and more subtle signs – if you can call them that, in retrospect – of increasingly restrictive measures to freedom of expression, the criminalization of research and historical inquiry, the rehabilitation of Stalin in the Russian school curriculum, along with the continued sharpening of the country’s secrecy laws.

Vadim and I began to work together closely after 2001, when the Swedish-Russian Working Group presented its final reports. We were a good match - Vadim with his singular expertise about the Soviet state security system and Russian archives, and I with my insights into the Swedish aspects of the Wallenberg case.

We focused our efforts to fill the obvious gaps in the official Wallenberg case record, mainly in Russia, but also in Sweden.

Two fundamental sets of questions had been left unanswered by previous investigations:

1. Why was Raoul Wallenberg arrested and why did Stalin decide not to release him?

2. What happened to RW after his trail breaks off in the spring and summer of 1947?

One of the biggest problems with the Wallenberg investigation was that - with certain important exceptions – the Russian side would provide only censored or partial copies of key records, including the pages of prison registers in Lefortovo and Lubyanka prisons - the two places where Wallenberg was known to have been incarcerated.

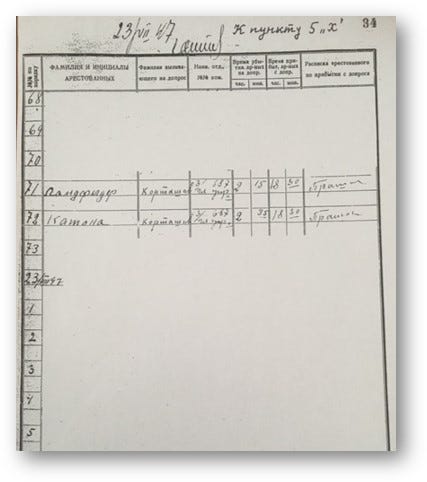

For more than ten years we conducted a courteous and professional correspondence with the Central Archive of the Russian Federal State Security Service (FSB). Right from the beginning, our efforts yielded important new insights. We were able to show that Wallenberg’s driver – the Hungarian citizen Vilmos Langfelder - and his cell mate Sandor Katona had not signed the interrogation register after a lengthy interrogation in July 1947 – suggesting that something serious must have happened during this session.

We discovered that Russian authorities had lied when they said that the file of Wallenberg’s long-time cellmate, the German diplomat Willy Rődel, was not preserved. As it turned out, it was preserved almost in full. Interestingly, the last page of this file consists of an envelope that contains Rödel’s diplomatic passport and his prisoner card. This raised the question whether or not Raoul Wallenberg’s file, too, has been preserved and if his personal possessions that were returned to his family in 1989 were, in fact, taken from this collection. Access to the archival dossier in which Rődel records were recovered remains restricted to this day.

Vadim’s crucial insights and “firsts” are too numerous to mention – he knew the system so well that he understood exactly what kind of records should exist and how to identify them. Vadim worked incredibly hard to move the Wallenberg case forward. He would spend countless hours composing requests, reviewing article drafts and legal briefs, translating them into Russian and then forwarding them via the Swedish Embassy in Moscow. It was in large part his dedication and nearly unmatched expertise that allowed us to keep the Raoul Wallenberg case in the forefront of public discussion and debate.

In 2009, these efforts yielded what is probably one of the most important and sensational pieces of information since the Soviet government’s announcement in 1957 (in the so-called Gromyko memorandum) that Wallenberg supposedly had died suddenly of a heart attack in his prison cell ten years earlier, on July 17, 1947. The FSB archivists informed us that a few days later, on July 23, 1947, a previously unknown numbered prisoner – Prisoner no. 7 – was interrogated for more than 16 hours in Lubyanka prison (along with Vilmos Langfelder). Circumstantial evidence strongly suggested that this prisoner was, in fact, Raoul Wallenberg – which meant that he would have been alive six days after his official date of death.

Worse, it is clear that Russian officials had intentionally withheld the information for decades, including from the Swedish-Russian Working Group that included Wallenberg’s brother. Yet, once again, Swedish officials did virtually nothing to follow up the new information. Two years later, they moved to bury the news (by classifying a crucial memo) that a top FSB archivist actually had confirmed to them in conversation that Prisoner no. 7 was indeed identical with Raoul Wallenberg.

The Russian position today is that even with best intentions, it cannot provide any additional information about Raoul Wallenberg’s fate. These claims have been sharply questioned by many other experts – but nobody has done as much to shatter the myth as Vadim.

Despite strong evidence to the contrary, Swedish officials, unfortunately, have accepted the official Russian position. In 2016, we presented an extensive catalogue of open questions for Russia. We later created a distilled list of the most urgent requests for documentation that the Russian side can and must present. Right before the pandemic, the FSB archive yielded on one of the most essential points and invited Wallenberg’s niece (Marie Dupuy) to review the requested prison register pages in Moscow. Unfortunately, due to the deteriorating political situation, that visit has yet to take place.

Vadim’s experience and deep trove of knowledge allowed him to prod and probe all possible avenues of inquiry.

Thanks to his study of internal Politburo records Vadim discovered that – contrary to earlier claims – as early as the spring of 1946, Stalin had signaled that he was eager to reduce political tensions with Sweden. It was the strongest indication yet that he almost certainly intended to use Raoul Wallenberg as an important bargaining chip or pressure point against Sweden. And that it may well have been possible to rescue Raoul. Vadim also showed that Stalin was almost certainly directly informed of Wallenberg’s detention in Hungary, in real time (from Budapest), via Soviet field intelligence and the Red Army Political Directorate (all records never explored by any official investigations) and that these communications must be preserved in Russian archives.

P R O T O C O L No. 50

(Special no. 50)

Of the POLITBURO of the CC VKP (b) DECISIONS from MARCH 6 – APRIL 11, 1946

From April 5, 1946

83. On our relationships with Sweden

[It is necessary] to make a move towards the Swedes and recognize the need to take the course for improving our relations with Sweden. For this purpose:

1.Charge Com.[rade] Chernyshev I. S. [Soviet Envoy to Stockholm] to make it clear to Minister for Foreign Affairs [Östen] Undén that in case of the successful development of the negotiations about the credit, favorable conditions for further positive political Soviet-Swedish relations will be created. [...] [emphasis added]

CC SECRETARY J. Stalin [handwritten signature]

[Source: Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (RGASPI, Moscow). Fond/Collection 17. Opis’/Inventory 162. Delo/File 38. Listy/Pages 37-38.]

Most notably, Vadim had a central role in exposing serious attempts at Russian disinformation, especially the false claims made by two former top-level KGB officers Pavel Sudoplatov and Ivan Serov, in their respective memoirs. This refutation was made possible only because of Vadim’s intricate knowledge of the inner workings of the Soviet state security apparatus and the complicated career paths of individual KGB officers.

On the Swedish side, too, we made enormous strides to fill some of the glaring gaps in the Wallenberg record.

We addressed the previously little understood problem of other Swedish citizens imprisoned in the Soviet Union (which led to confusion with Raoul Wallenberg and resulted in serious misinterpretations of numerous witness testimonies).

We uncovered important new details about Raoul Wallenberg’s personal and professional background including the contacts with his famous relatives, the powerful Wallenberg business family. We also shed additional light on some of the complex circumstances leading to Raoul’s selection for the Budapest mission.

And I am proud to say that our paper on previously unknown Swedish-Hungarian intelligence connections is among the most widely read historical papers on the academia.edu website.

In August 2019 we were honored to submit our findings in an official report to the Swedish parliament, mapping out a detailed roadmap for continuing the Wallenberg inquiry and for solving the case.

I catch myself every day, thinking “I should ask Vadim about this” or half-forwarding a news item or interesting Tweet – his passing leaves a huge hole that is impossible to fill, especially in the life of his loved ones. Vadim, you leave behind a wonderful legacy as a father, husband, scientist and historian. Your voice and your work will remain with us. They are sure to continue to make their lasting mark in the years ahead. Rest in peace.