The Swedish Security Police suspected that Swedish Ambassador Rolf Sohlman’s longtime backchannel to the Soviet leadership was one of the KGB’s most ruthless foreign agent recruiters

Susanne Berger February 20, 2024

The long serving Swedish Ambassador to Moscow Rolf SOHLMAN was feared to have a close association with Colonel Panteleymon Ivanovich TAKHCHIANOV (codename “Hasan”), one of the KGB’s most notorious and experienced counterintelligence officers. Reports about their exchange, including in the Raoul Wallenberg case, must continue to exist in Russian archives.

The information emerged as part of an in-depth review of documentation found in the archive of the Swedish Security Police (SÄPO) as well as the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Sohlman and his contact, who pretended to be an academic residing in Moscow, discussed the most sensitive issues of state, including new and highly secret developments in the Raoul Wallenberg case during the years 1961-1964.[1] The person alleged to be Takhchianov apparently used a pseudonym in his dealings with Sohlman. It is unclear if Sohlman was aware of the true identity of his contact whom he referenced in official correspondence simply as “my academic friend”. It is equally unclear if Sohlman at any point was operating under duress. However, the KGB’s alleged use of such a senior officer suggests not only a well-planned operation, approved at the highest official levels, but a possible attempt at recruitment.

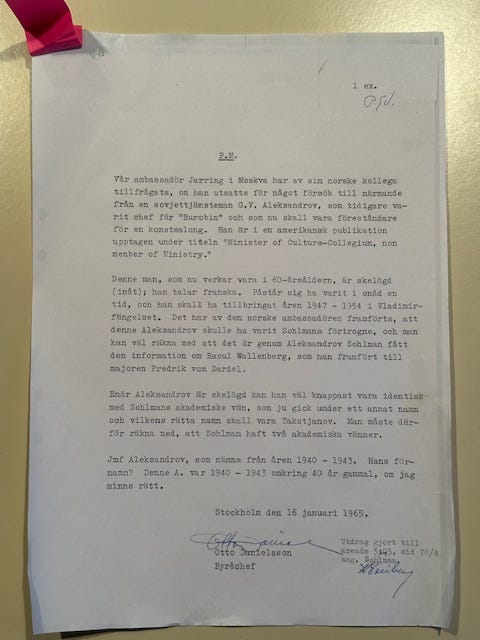

In an internal memorandum dated January 16, 1965, the senior Swedish Security Policy official Otto Danielsson - the man who was in large part responsible for the arrest of Soviet agent Stig Wennerstrőm a year and a half earlier - identified Sohlman’s contact as a man “whose real name is supposedly ‘Takstjanov’.” [2] This was undoubtedly Panteleymon Ivanovich Takhchianov, a former officer in the Soviet state security services (the OGPU, predecessor of the MGB and later the KGB), and a specialist for state-sponsored executions - the secret assassinations of political dissidents at home and abroad. He was also a top recruiter of foreign assets for the Soviet state security services during the 1940s and early 50s.

Sohlman’s contact with his “academic friend” over the course of several years in the late 1950s and early 60s raises serious questions about how the Soviet side hoped to influence the official handling of the Raoul Wallenberg case and other key Swedish Cold War mysteries. It also offers a strong indication that additional records remain in both Russian and Swedish archives that could help to fully clarify the lingering questions about Wallenberg’s fate, as well as the cases of other Swedish citizens imprisoned in the Soviet Union. The file of at least one of these individuals remains strictly classified in the archive of the Swedish Security Police.

At issue in the discussions between Ambassador Sohlman and his confidential contact were the sensational but unconfirmed (and at the time highly secret) reports by Swedish Professor Nanna Svartz that in January 1961, the prominent Soviet physician A. L. Myasnikov had informed her that Raoul Wallenberg was alive in the Soviet Union. This challenged the official Soviet government claim [from February 1957] that Wallenberg had died suddenly in his prison cell in Moscow on July 17, 1947. Myasnikov disputed Svartz’s statements, and the issue was never resolved.

Rolf Ragnarsson Sohlman - one of Sweden’s top diplomats

Rolf Ragnarsson Sohlman was one of the most successful and highly regarded Swedish diplomats, with numerous foreign service postings (including London, Riga, Moscow and Paris) to his credit and a special expertise in international trade issues. When he arrived in Moscow in 1947, he brought much needed stability to a Swedish mission that had suffered under Staffan Söderblom’s controversial tenure (1944-46). Söderblom’s successor, Gunnar Hägglöf accepted his assignment only reluctantly. He postponed his arrival for seven months and departed shortly afterwards.

Sohlman served in the post as Swedish Ambassador to Moscow for seventeen years (1947 – 1964), an exceptionally long time. He possessed a deep knowledge of the Soviet Union, grounded in personal experience. His father, Ragnar Sohlman, was a leading chemical engineer for companies associated with the Swedish inventor and businessman Alfred Nobel.[3] In 1924, Rolf Sohlman helped to distribute food and other supplies to needy civilians in Crimea. In connection with this aid mission (organized under the League of Nations), he met and later married his wife Zinaida (Zina) Yarotskaya, daughter of Alexander Yarotsky, a prominent professor of medicine.

Sohlman was a close friend and associate of Swedish Foreign Minister Ȍsten Undén. For almost two decades, they together shaped and implemented a policy approach to the Soviet Union that was designed to emphasize Sweden’s role as a “bridge builder” and a neutral player between the post World War II superpowers. Sohlman consistently aimed to assure the Soviet leadership of the Swedish government’s peaceful intentions, thereby shielding Sweden from Soviet aggression. Some critics considered Sohlman’s reporting from Moscow and especially his assessment of Soviet intentions overly optimistic and uncritical. [4] Erik Boheman, Sweden’s Ambassador to London and subsequently to the U.S., apparently went so far as to suggest that Sohlman felt it might be better for Sweden not to defend itself if it were attacked by the Soviet Union.[5] In 1956, the CIA recommended a discreet inquiry into Sohlman’s views and associations.[6] Still, most observers felt that while he clearly had pro-Russian views, he was smart and most importantly loyal enough not to make any serious concessions to the Soviet government.[7]

Sohlman’s official correspondence from 1949-1962 remains partly inaccessible in Riksarkivet. Sohlman’s personal dossier in SÄPO is strictly classified, as is the file of his wife Zinaida. Not even partially censored documents have been released. However, some interesting details have emerged through the years.

Given the fact that Swedish security law stipulates a proscription period of 70 years for official records (and in some cases up to 90 years) relating to foreign affairs, the file appears to not have been created until the 1950s.

Some of the suspicions against Sohlman were clearly connected to his wife Zinaida whose family remained in the Soviet Union. She later recalled how she was painfully aware that her relatives were the target of official Soviet pressure. She provided a vivid account of how this caused her great personal anxiety and stress. Her sister lived close to the Swedish Embassy in Moscow, yet the two were unable to see each other. “I was like a living corpse,” Zinaida later recalled in a letter. “I lived close to my loved ones but with no hope of ever seeing them again.” [8]

A clear security risk

An entry from September 4, 1963, in Swedish Prime Minister Tage Erlander’s diary confirms that by then Sohlman was designated a clear “security risk”.[9] "Saddest [news] yesterday,” Erlander wrote. “Discussion at 16.30 about [Rolf] Sohlman and [Sverker] Åström ... Sohlman was named as a security risk.”

There were three major reasons for the suspicions against Sohlman - all circumstantial, but nevertheless serious.

First, Swedish Air Force Colonel Stig Wennerström who was arrested in the summer of 1963 as a Soviet agent, reported that during one of his visits to Moscow he observed how Sohlman’s wife had personal access to the Swedish Embassy safe. He also told his Swedish Police interrogators that when he was stationed in Moscow in 1949, his Soviet contacts had no interest in any information about the Swedish Embassy, because they received information from “a higher level.” [10] The only individuals at a “higher level” than Wennerström in his position as Air Attaché would have been one or two people, including the Military Attaché Juhlin Dannfeldt and Ambassador Sohlman and his wife.

Second, an earlier investigation by SÄPO into the security protocols at the Swedish Embassy, Moscow found that Sohlman had a shockingly cavalier attitude towards security and that numerous individuals with ties to the Soviet State Security Services had frequent and unsupervised access to the Embassy premises.[11] SÄPO concluded that the KGB was able to read the Swedish ciphers (encoded message) for the years 1961-62 sent between Stockholm and Moscow, and possibly as far back as 1954. Sohlman surely must have been aware of the risks.

A few years ago, it emerged that SÄPO had received information about Sohlman from the Soviet defector Anatolii Golitsyn. [12] Golitsyn (alias Klimov) who defected in December 1961 claimed that the KGB was to have made a serious attempt in 1958 to compromise Sohlman via his former mistress Domnika Cesianu (code name “Dzheta”). Earlier attempts to approach Sohlman and his wife had apparently been unsuccessful. In 2021, the former Chief Legal Advisor to the Swedish Foreign Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Professor of International Law Bo Theutenberg obtained partial confirmation of Golitsyn’s claims from the V. Mitrokhin archive in London [13] It is unclear if Golitsyn also was the source about Sohlman’s alleged contact with P.I. Takhchianov or when exactly the Swedish Security Police first received this information.

The alleged KGB approach came at a sensitive time in Swedish Soviet relations which cumulated in Soviet Premier’s Nikita Khrushchev canceling his planned trip to Scandinavia in July 1959, due to what he called a prevailing “anti-Soviet atmosphere”.

“A direct line to Khrushchev”

The KGB appears to have succeeded in its attempt to get close to Sohlman. Documents in the archive of the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs show that for many years, Sohlman had contact with a Soviet citizen he identified only as an “academic friend” living in Moscow. Especially during the early 1960s Sohlman’s official correspondence is replete with references to meetings and the confidential exchange of information with this well-placed contact who seemed to have access to the highest levels of the Soviet leadership.

In an internal memorandum dated January 16, 1965, the senior Swedish Security Policy official Otto Danielsson - the man who was in large part responsible for the arrest of Soviet agent Stig Wennerstrőm a year and a half earlier - identified Sohlman’s contact as a man “whose real name was ‘Takstjanov’.”[14] This was undoubtedly Panteleymon Ivanovich Takhchianov, a former officer in the Soviet state security services (the OGPU-NKVD, predecessor of the MGB and later the KGB), and a specialist in secret executions - the state sponsored assassination of political dissidents at home and abroad. He was also allegedly a top recruiter of foreign assets for the Soviet state security services during the 1940s and early 50s.

Sohlman disclosed his close contact with the presumed academic to his superiors in Stockholm who apparently approved of the unofficial exchange and regarded him as an important back channel to the Soviet government. [15]

1958 - the year of the KGB’s alleged approach to Sohlman - in many ways constituted a benchmark in the Soviet Union’s relations with the West. Swedish Soviet relations had seemed at a low point just a short while earlier, mainly due to the Soviet Union’s brutal crushing of the Hungarian revolution in 1956. There were serious bilateral strains because of Moscow’s sudden revelation in March 1957 of Sweden’s post-war espionage network in the Baltic states, plus the earlier downing of two Swedish aircraft in 1952 and the unexplained loss of several Swedish ships in the Baltic Sea, not to mention the lingering questions in the Raoul Wallenberg case. [16] But also slowly a new dynamic seemed to build. Nikita Khrushchev had become head of the Soviet government, after condemning Stalinist crimes. Industrial production and Soviet living standards were on the rise, and the Soviet Union had just successfully launched its first satellite into space. Like many others, Sohlman felt the “new Russia” was on an inevitable ascent. More skeptical and critical views – about questionable economic data, the proliferation of nuclear weapons and the potential impact of the recently created Warsaw Pact alliance - were largely blended out. [17]

Just as importantly, the approach to Ambassador Sohlman coincided with the promotion of Oleg Mikhailovich Gribanov in 1956 to head the KGB’s Second Main Directorate (counterintelligence). Gribanov was known as an anti-Western hawk, with a focus on compromising foreign dignitaries. In his work, he employed highly creative means, ranging from flattery to violence. He made use of both male and female actors to achieve his aims. He was also known to rely on the vast pool of retired KGB reserve officers.

Sohlman as well as his superiors must have suspected that his “academic friend” was in contact with or possibly a member of the Soviet intelligence services. However, there are indications that Sohlman may have actually believed that his source either had separate lines of access to the Soviet leadership, potentially distinct from the Soviet state security apparatus, or that his “friend” was no longer an active member of the security services. At one point, he justified sharing highly sensitive details in the Raoul Wallenberg case with his “academic friend” because of the urgency of the matter at hand. "After all,” Sohlman wrote, “one cannot be completely sure that they [the Soviet leadership – SB] would receive the information necessary to assess the new situation in time through their intelligence services." [18]

It should be noted that any direct access to individual Soviet leaders as claimed by Ambassador Sohlman’s confidential contact would have been virtually impossible. Even a top-level KGB agent like [Panteljemon Ivanovitj] Tachtjianov would have reported first and foremost to his superiors in the KGB, i.e. Oleg Gribanov. Key members of the Soviet Politburo would have been apprised of the discussions, but there would have been no direct exchange.

Top secret discussions

Confidential backchannel discussions and contacts are the bread and butter of diplomacy. Nevertheless, it is striking that Sohlman and his contact exchanged information not only about the most secret details in the Wallenberg investigation, but also - in real time - about highly sensitive and current Swedish and Soviet espionage matters. This included the case of Karl Johan Fast and those of two recent Soviet defectors at the time - an alleged Soviet agent named “Lybin” (Arvo Löbin, a Soviet naval officer from Estonia) and a man named Rostislav Leonidovich Tkatchev (Tkachev).

Karl Johan Fast was a Swedish (IB) agent and sea captain who was imprisoned in Leningrad on suspicion of espionage in October 1960. He was trained to collect photographic intelligence on Soviet vessels and maritime installations in the Baltic Sea. Sohlman helped to negotiate Fast’s release and he returned home in March 1961. His case is virtually unknown in Sweden and remains so sensitive that his file has stayed completely classified in the archive of the Swedish Security Police. Fast had to sign an agreement to stay silent for 40 years. As part of their discussions about Fast, Sohlman’s “academic friend” informed the Ambassador that he could show him “long lists of Swedish agents, working also for the Anglo Saxons”. All this must have suggested to Sohlman that his interlocutor definitely had privileged insights into intelligence matters. [19]

At the time of his arrest, Captain Fast had in his possession in his ship's cabin a modern camera and several rolls of film showing images of Soviet naval vessels, port installations, as well as blueprints of the Soviet Union's very latest submarine. But despite that, he was never charged with espionage. Instead, he spent only five months in Soviet prison on a trumped-up charge of attempted rape before being allowed to return home to Sweden. So, what prompted the relatively mild Soviet government’s treatment of Fast?

According to the new documentation found in the Swedish National Archives, it appears that as part of their discussions about Captain Fast, Sohlman's academic friend asked if Swedish authorities could help locate a Soviet defector named Rostislav Leonidovich Tkachev who was a translator and instructor in the Soviet Communist Party's youth organization Komsomol. At this point, however, the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs' legal department protested and objected in formal terms to any Soviet attempts to link the two cases.

"We protest against the principled connection (see tel. 341 Moscow, 24.11.60) of the Fast case with the Tkachev case, which is - as was previously pointed out by the Swedish side - completely different," Love Kellberg, the head of the MFA’s legal department wrote.

Even in the Raoul Wallenberg case, the Swedish government steadfastly refused to link the question of his fate to other cases or topics, despite having several chances to do so. One of the best opportunities came when Stig Wennerström was arrested as a Soviet spy in the summer of 1963, when Rolf Sohlman was still ambassador in Moscow.

Nevertheless, the timeline in the Karl Johan Fast case suggests that the parties may have struck a spoken or unspoken agreement of some type:

On January 18, 1961, Rostislav Tkachev suddenly returned from Sweden to the Soviet Union and was almost certainly immediately detained.

A month later, in February 1961, a Swedish embassy official in Moscow received permission to visit Fast in prison for the first time. (The visit was connected to his pardon application.)

Then, on March 16, 1961, Carl Johan Fast was released and traveled home to Sweden.

On March 28, 1961, Tkachev was charged with treason under Article 64 of the Soviet Criminal Code. "Treason; that is to defect to the enemy, to spy …/… to flee abroad or to refuse to return to the USSR from abroad.” Tkachev was sentenced to 15 years in prison but served only two years. He was released in 1963.

Sohlman’s “academic friend” appears to have valued the Ambassador as a source. When Sohlman was about to leave Moscow in late 1963, he informed Stockholm that his contact had expressed strong “irritation” about Sohlman’s reassignment which he considered “inexplicable”. [20]

A routine back channel or a KGB recruitment operation?

If Sohlman’s contact was, as alleged, P.I. Takhchianov, it is worth taking a closer look at the latter’s background. Takhchianov’s history raises questions about whether the exchange of information would have been as open and reciprocal as it is generally portrayed in Sohlman’s reporting or if Sohlman felt any pressure to cooperate. According to a short biographical sketch published in 2006 by Stanislav Lekarev, one of Takhchianov’s former colleagues, Takhchianov’s sophisticated and elegant façade obscured a ruthless and highly volatile personality.

According to biographical information compiled by Nikita Petrov, senior historian and co-chairman of the Moscow Memorial Society, Takhchianov - codenamed HASAN – was born into a Greek peasant family in the village of Verishan (now part of Turkey) in 1906.[21] He joined the OGPU in 1932. A year later he was sent abroad as an illegal, and in 1936 settled in France, as a Turkish immigrant.[22]

British historian Boris Volodarsky relates how Takhchianov in 1938 seemingly played a central role in the abduction and murder of a high-ranking OGPU official named Grigory Sergeyevich Arutyunov, a.k.a. Georges Agabekov. [23] He was lured to a safe house and stabbed to death. “Agabekov's body was stuffed into a suitcase, thrown into the sea, and never found.” [24] By 1949, Takhchianov headed Department 2 of the Second Main Directorate (counterintelligence) of the Soviet Ministry of State Security (MGB). He died in 1977.

Takhchianov, who ultimately rose to the rank of colonel, became an early pensioner in 1953 and settled in Moscow. This means he could have been called out of retirement for certain special assignments and recruitment operations. Clearly, such a step would have required extensive discussion and planning at the highest levels of the KGB as well as the Soviet political leadership. One would not have undertaken such an operation lightly. “Takhchianov’s alleged activity against employees of European embassies can be explained by the fact that after 1945 he worked in counterintelligence and specialized in the embassies of European countries in Moscow,” says Russian historian Nikita Petrov. “After retirement, while staying in Moscow, he could of course continue to carry out tasks on behalf of his former colleagues.” Boris Volodarsky is more skeptical. “I doubt very much that Takhchianov could have been assigned the task of approaching Ambassador Sohlman," he told me. "First, because he had already been a pensioner for quite some time and second, more importantly, he was a KGB assassin and dealing with foreign ambassadors was not exactly his specialty." However, based on the evidence, Volodarsky agrees that the KGB apparently made a successful attempt to introduce a person who gained close access to Sohlman and who regularly discussed highly sensitive information with him. Reports about these conversations must continue to exist in Russian archives.

“Take my bloody hand”

In a 2006 article published in Argumenty Nedeli, the former Soviet intelligence officer Stanislav Lekarev who worked with Takhchianov in the early 1950s describes him as highly intelligent, with a special aptitude for languages. Impeccably dressed, he made a lasting impression on those he met. Even allowing for some exaggeration in Lekarev’s account, Takhchianov was clearly not a man to be trifled with. Lekarev portrays him as a no-nonsense recruiter of foreigners who had encountered difficulties in one way or another during their stay in the Soviet Union - a rare skill that led to special assignments even in retirement, Lekarev wrote. Takhchianov reminded him of “Don Corleone”, Lekarev added, a Mafia-style enforcer who did not shy away from using violence to get his point across, and who often greeted his associates, only half-jokingly, with one hand outstretched: “Take my bloody hand!”

In his article Lekarev offered a harrowing description of Takhchianov at work, confronting an unnamed African diplomat who had run into some type of trouble. [25] With the help of his subordinates Takhchianov supposedly staged a scene at a restaurant in Moscow that not only frightened the African diplomat, but even left Lekarev shaken.

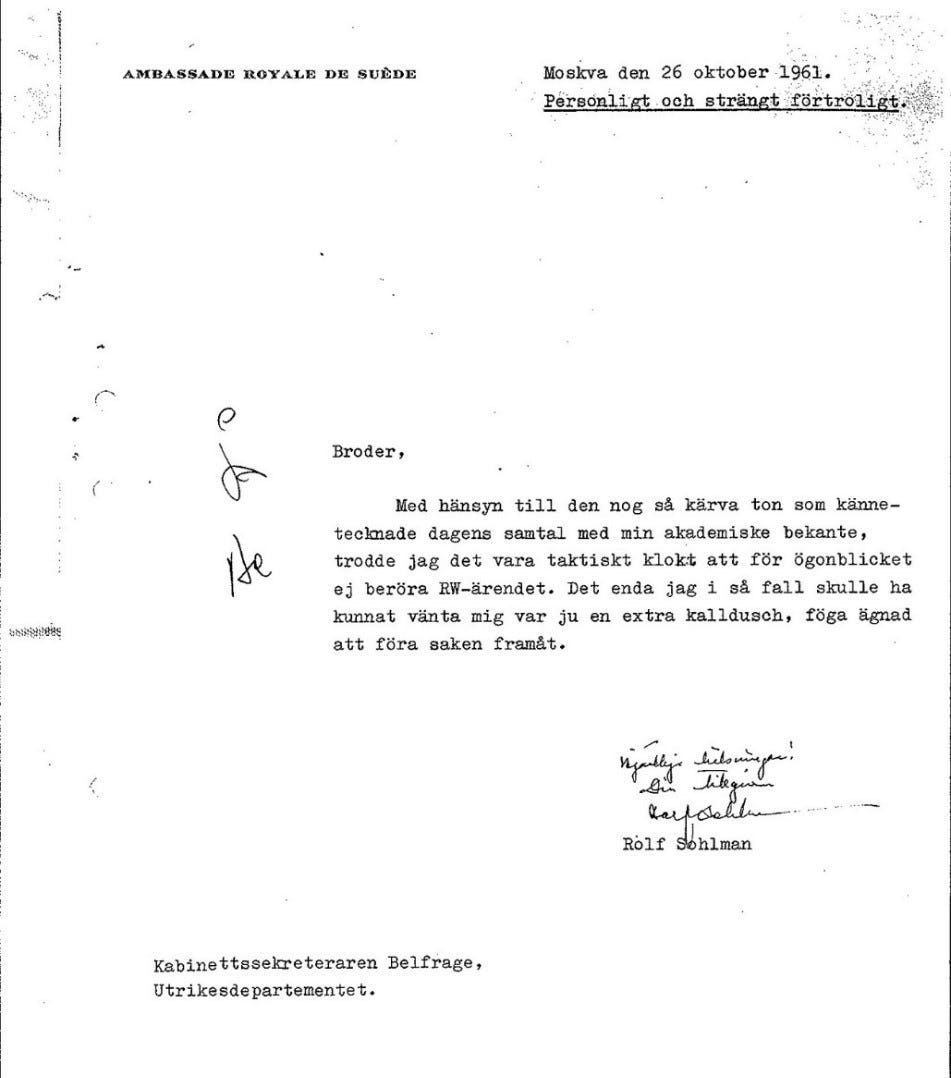

There is no indication that Sohlman’s “academic friend” used similar aggressive methods in his dealings with Sohlman. Their exchange appears to have been far more civil. However, it is clear from Sohlman’s reports that his “academic friend” did not hesitate to express serious disagreement with Sohlman’s (and, by extension, the Swedish government’s) position throughout the months and years of intense discussions in the Wallenberg case and even occasionally flashed signs of strong anger and annoyance. [26] In October 1961, Sohlman informed Swedish Cabinet Secretary Leif Belfrage that he would stop raising the Wallenberg case for a while. “Given the rather harsh tone that characterized today's conversation with my academic acquaintance,” Sohlman wrote, “I thought it tactically wise not to touch on the Raoul Wallenberg case for the moment. The only thing I could have expected in that case was an extra cold shower, not well suited to moving things forward.”

Sohlman’s contact also did not shy away from voicing implicit criticism of the Swedish government – such as when he pointedly directed Sohlman to a recently published article about the Wallenberg family’s role in various separate peace initiatives pursued by Nazi Germany during the Second World War.[27]

As early as November 1962, Sohlman's contact had requested to "delete [the Wallenberg case] as well as other old cases" from the official agenda of the two countries. Sohlman stated "that something like that is not possible in the Wallenberg case." Professor Nanna Svartz's personal reputation and the seriousness of her account made it impossible for the Swedish authorities not to follow up on her statements, even though they were met with strong reactions from the Soviet side.

Ambassador Sohlman did not directly object to continuing to raise the Wallenberg case through his Soviet contacts, but on numerous occasions he expressed his personal skepticism to his colleagues at the Swedish Foreign Ministry. He also repeatedly stressed the warnings his academic friend issued in their conversations that similar discussions could have serious consequences.

It should be emphasized, however, that these tenser moments did not stop Sohlman and the Swedish government from continuously raising the question of Raoul Wallenberg’s fate with Soviet representatives, including during Nikita Khrushchev’s official visit to Sweden in 1964. Sohlman also personally met repeatedly with Wallenberg’s parents, including twice in the summer of 1963, informing them that the Swedish government had received information that Raoul Wallenberg was alive in 1961 and had received “medical care”.[28] Sohlman based this information on the above-mentioned reports by Professor Svartz about her meeting with a Soviet colleague in January 1961.

Sohlman and the Swedish government pursued Svartz’s testimony even though Sohlman’s contact repeatedly insisted that Raoul Wallenberg was “dead” or “did not exist” any longer, referring repeatedly to the official Soviet government statement from February 6, 1957. [29]

In summary, Sohlman’s alleged contact with Takhchianov raises important questions about how the Soviet side hoped to influence the official handling of the Raoul Wallenberg case and other key Swedish and also international policy issues of the day, and on what terms exactly Sohlman and his contact agreed to exchange information. It would also be of interest to learn more about what kind of messages exactly Sohlman himself may have tried to convey discreetly through this channel.[30]

“Aleksandrov” – a mutual acquaintance of both Rolf Sohlman and Sverker Åstrőm

Interestingly, Danielsson’s memo from January 1965 that identified Takhchianov as Sohlman’s “academic friend” was not filed in Sohlman’s dossier but in the file of Sverker Åström (H.A. 901/55). This was because it mentioned a second Soviet official – a man supposedly called “G.V. Aleksandrov” who had been in contact with both Åström and Sohlman during the early 1940s and late 1950s respectively.[31]

At the time, Åström was another top Swedish diplomat suspected of being a Soviet asset. In 1965 Åstrőm served as the Swedish Ambassador to the United Nations, after having been denied a promotion to become Sohlman’s successor in Moscow, due to the suspicions against him. From 1956 until 1963 he headed the powerful Political Department of the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A protégé of Swedish Foreign Minister Undén, Åstrőm was considered to be one of the leading experts on the Soviet Union who had the ear of the Swedish political leadership.

Ten years earlier, in 1954, the Soviet defector Vladimir Petrov, along with his wife, Evdokia Petrova (both were Soviet foreign intelligence officers), had told Australian officials about two presumed Soviet agents in Stockholm, one a high military officer, the other a diplomat known by the Russian code name “Osa” (“Getingen” or “Wasp” in English). Otto Danielsson’s personal notes confirm that SÄPO suspected Åström to be identical with “Osa/Getingen”. [32]

Sohlman’s and Åstrőm’s Soviet contact “Aleksandrov” was almost certainly Vladimir Aleksandrovich Aleksandrov, an artist and architect, and a well-known figure in Moscow. [33] In the early 1940s, he held a prominent position in the so-called Foreigners Bureau (BYUROBIN, later UPDK) that operated under the authority of the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MID). The agency was responsible for contacts with foreign diplomats, and, in particular, for the rental and maintenance of the city’s foreign legations, as well as their supply of furnishing and food.[34]

Unbeknownst to Danielsson, Sohlman already in 1960 reported a meeting with Aleksandrov at the Swedish Embassy, Moscow to Stockholm. Sohlman asked Aleksandrov, whom he described as “highly educated”, about his time in Soviet imprisonment. Aleksandrov was arrested in 1948 and spent over six years in Vladmir Prison (1949-1955), one of the Soviet Union’s most important punishment and isolator prisons. [35] Aleksandrov told Sohlman that he had never heard of Wallenberg while he was held there. [36] Sohlman was clearly very aware of Aleksandrov’s role and position, as he explained in his report to Stockholm. Aleksandrov’s task before his arrest appears to have been to collect specific information about certain foreigners, “their likes and dislikes, interests and character ... rather than [to conduct] a detailed surveillance,” Sohlman wrote. [37] According to both Nikita Petrov and Boris Volodarsky, Aleksandrov clearly was connected to the MGB/KGB.

During the Wennerström inquiry, Aleksandrov’s name had come to light as one of Åström’s contacts in Moscow back in 1941.[38] As such, there was nothing surprising about this. In 1941, as Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union, BYUROBIN (and presumably Aleksandrov), was overseeing the evacuation of foreign diplomats from Moscow to Kuibyshev. [39] It was well known that the Soviet state security services went to great lengths to compromise foreign diplomats, including in Kuibyshev. [40]

It would be interesting to know if Åström ever met with Aleksandrov during his subsequent visits to the Soviet Union – for example, in March 1945, when he accompanied the former Soviet Ambassador to Sweden Alexandra Kollontay home to Moscow; or in 1959, when he visited the Soviet Union as head of the Swedish Foreign Ministry’s Political Department, on a lecture tour.[41] Possibly more important is the question if Åstrőm ever met Sohlman’s “academic friend” or other Soviet intelligence representative during his trips to Russa. As a visiting Swedish diplomat, Åstrőm was a guest of Ambassador Sohlman and his contact was known to visit the Embassy occasionally. So far, the crucial years of Åström’s Swedish Security Police dossier remain inaccessible.

Sohlman and Åström’s conditional reassignment in 1964

As a result of SÄPO’s designation of Rolf Sohlman and Sverker Åstrőm as a national security risk, both men were reassigned to new posts: Åström became the Swedish UN representative in New York, while Sohlman was installed as Ambassador to Denmark. However, in both cases a deal appears to have been struck that allowed each of them to assume more responsible and sensitive posts in the future, despite the lingering suspicions against them. Unlike Stig Wennerstrőm, neither Sohlman or Åstrőm had been caught “red-handed”, and many leading figures in the Swedish political establishment were willing to extend them the benefit of the doubt. As Tage Erlander noted in his diary, regarding Åström’s planned reassignment,

“It must be terrible to be forced to take a stand on Åström's promotion, when the police so insistently warn against it. But now Olof Palme says that Åström would prefer to be away for a few years and then come back as cabinet secretary [emphasis added]. Then the most appropriate thing would probably be to move Agda Rössel, who – still according to Palme – does not have the energy to be [UN] ambassador.”[42]

It appears that the parties arrived at some kind of a spoken or unspoken understanding, perhaps facilitated by Olof Palme (who at the time served as Minister without portfolio and advisor to the government), that Åström would eventually become Cabinet Secretary, if he agreed to a lesser post now. Åström may well have held Palme to this agreement when the latter became Prime Minister in 1969. Palme finally named Åström to the highly sensitive position of Cabinet Secretary in 1972.

Similarly, Rolf Sohlman accepted a temporary position as ambassador to Denmark after his removal as ambassador to Moscow. [43] He clearly was unhappy with his demotion, as is evident from his comments in his normally very formal and restrained official communications of the time. A year later, he was assigned as ambassador to Paris when the position became vacant. Sohlman died as the result of sudden heart failure in 1967. It is somewhat ironic that Sohlman ended his career in the country whose long-time Ambassador to Moscow Maurice Dejean had been compromised in Moscow in 1956 - by the very same group that targeted Sohlman.

Top-level Swedish police and intelligence officials, as well as certain members of the Swedish political leadership undoubtedly have been aware of Sohlman’s presumed involvement with a confidential Soviet contact presumed to be Takhchianov. Yet his name has not been mentioned in the numerous memoirs published by former security police officials, including the two-volume memoir of Otto Danielsson’s successor Olof Frånstedt. Perhaps Frånstedt was hesitant to disclose information that was still classified in 2014 when he published his book. He also did not mention Golitsyn’s allegations (of which he must have been surely aware), about the KGB’s attempts to possibly compromise Sohlman via his former mistress.

It is possible that back in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Swedish Security Police officials may not have had a clear understanding who exactly Sohlman’s “academic friend” (believed to be Takhchianov) really was or how far the alleged contact with Sohlman had actually advanced. It is also possible that Swedish Security Police officials eventually obtained information that Sohlman’s “academic friend” was not identical with Takhchianov after all, and/or that the suspicions against Sohlman had proven to be unfounded. A possibility that cannot be entirely excluded is that Sohlman functioned at some point as a source for Swedish intelligence and that he was therefore shielded from further inquiries. In 1963, during testimony given as part of the Wennerstrőm investigation. the Swedish Superintendent of Police Georg Thulin confirmed Sweden’s use of double agents as far back as the early 1940s. The identity of these individuals remains unknown. [44]

Serious consequences for the Raoul Wallenberg investigation

Since Sohlman’s back-channel contact with a supposedly well-placed retired Soviet academic was well known among Sohlman’s colleagues and he was removed from his post in late 1963, the full implications may not have been thoroughly examined or recognized at the time. It is time to do so now.

For 20 years, from 1944 -1964 Sverker Åström and Rolf Sohlman played an integral part in coordinating the Swedish government’ official policy vis-à-vis the Soviet Union, including Sweden’s official approach to the Raoul Wallenberg case. Regardless if Sohlman’s “academic friend was, in fact, Takhchianov or not - Sohlman’s sustained contact with a highly placed Soviet representative and possibly a top MGB/KGB recruiter raises important questions and concerns.

Nealy 80 years after Raoul Wallenberg’s disappearance in Hungary Swedish authorities must disclose once and for all what his and also Sverker Åström’s contacts with Soviet representatives truly entailed. It needs to be clarified if and how Sohlman’s alleged contact with a top-level KGB officer influenced the official Swedish handling of the Raoul Wallenberg case, as well as other unsolved Cold War cases, not only during the 1960s but also in subsequent years. The same question presents itself for other key policy issues of the period. Raoul Wallenberg’s nieces Marie von Dardel-Dupuy and Louise von Dardel emphasized this point in their application to SÄPO in 2021:[45]

“In Sweden, the unresolved suspicions about Mr. Åstrőm and other officials, like the longtime Swedish Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Rolf Sohlman, have become normalized. This is an unacceptable situation.”

They further added that if the suspicions against Sverker Åstrőm and Rolf Sohlman are known to be false, the two men deserve to be publicly exonerated.

Sohlman’s alleged contact with Takhchianov involved discussions in the Raoul Wallenberg case at the highest levels of the Soviet leadership for more than three years. In their exchanges they also touched upon cases of other Swedish citizens, including individuals and agents detained in the Soviet Union of whom the Swedish public and researchers are currently not aware or only have a limited understanding. Sverker Åström, as head of the Swedish Foreign Ministry’s Political Department had direct knowledge of these discussions. It must be urgently determined if there are other, previously unknown cases of Swedish citizens or agents in Soviet imprisonment; when and where these individuals were detained; and what happened to them (date of release or date of death). Another important question is if the continued secrecy about these cases in any way affected the official bilateral Swedish Russian Working Group investigations of the 1990s. [46]

Sohlman and also possibly his wife Zinaida must have been debriefed by Swedish Security Police officials once they learned of the allegations made regarding Sohlman’s contact with a man believed to be Takhchianov and Golitsyn’s claims about KGB efforts to compromise Sohlman via his former mistress. The interviews could shed light on the precise subjects under discussion between Sohlman and his “academic friend”.

Sohlman’s source undoubtedly reported regularly to his superiors on his contacts with Sohlman and he must have also received instructions in return. Documentation about these exchanges, especially in the Raoul Wallenberg case, should continue to exist in Russian archives. The record may well contain additional information or clues about the official Soviet and later the Russian handling of Wallenberg’s fate. Operational records of the Soviet state security services remain generally completely inaccessible, but Russian officials certainly would be able to review the collection.

The new findings underscore once again the power of research - in particular the fact that important historical records continue to exist in Russian, Swedish and other international archive collections and that one of the oldest missing person cases can almost certainly be solved. Eight decades after Wallenberg’s disappearance, there is an urgent need for transparency and unhindered access to information.

I dedicate this article to my friend and colleague Dr. Vadim Birstein (1944-2023).

[1] See the archive of the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, P2 EU 1, Raoul Wallenberg case file, Specialdossier 1, 1961. In early 1961, Professor Nanna Svartz of Sweden reported that her Russian colleague, Professor A. L. Myasnikov had revealed to her during a meeting that he possessed direct knowledge of Raoul Wallenberg‘s presence in the Soviet Union. Sohlman and his “academic friend” apparently also discussed individual cases of Swedish and Soviet espionage (“Affären Fast”, “Fallet Lybin”). See Sohlman, March 18, 1961. Interestingly, the case of Karl Johan Fast remains fully classified in the Swedish Security Police archive. So does the file for Arvo Lybin (Löbin), a Soviet naval officer who defected in 1959. He left Sweden in 1960 with unknown destination.

[2] Memorandum signed by Swedish Security Police official Otto Danielsson, dated January 16, 1965, in the personal dossier of Sverker Åström (H.A. 905/55). The document was part of a set of records provided to me by the archive of the Swedish Security Police in a response to a request filed in 2022.

[3] In 1897, Ragnar Sohlman was appointed as the executor of Alfred Nobel’s will and served as director of the board of the Nobel Foundation for 46 years (1900-1946).

[4] See Sven Grafström. Anteckningar: 1945-1954, pp. 811-12, cited in Ingeborg Løkling. Våpenbrødre? Norge og Finland i svensk sikkerhetspolitikk, 1948-1949 [Brothers in Arms? Norway and Finland in Sweden’s Security Policy 1948-49. Master’s Thesis, The University of Oslo, Spring 2023. About the criticism of Rolf Sohlman by some of his Swedish diplomatic colleagues see also Karl Molin. Omstridd neutralitet: experternas kritik av svensk utrikespolitik 1948–1950 [Controversial Neutrality: The Experts’ critique of Sweden’s foreign policy 1948-1950]. Stockholm: Tiden, 1991, pp. 30-37. Sven Grafstrőm, head of the Political Department of the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and later Sweden’s Ambassador to the United Nations, liked to refer to the Sohlmans as “the couple Solmansky”. Wilhelm Agrell. Fred och fruktan: Sveriges Säkerhetspolitiska Historia 1918-2000 [Peace and Fear: History of Sweden’s Security Policy 1918-2000], Lund: Historiska media, 2000. p. 93

[5] Karl Weigelt. VSB-paktens tilkomst i ljuset av den svenska diplomatiska rapporteringen från Helsingfors och Moskva november 1947- april 1948 [The creation of the VSB Pact in the light of the Swedish diplomatic reporting from Helsinki and Moscow, November 1947- April 1948], Bachelor Thesis, Stockholms universitet, 1992, p. 14. When Boheman learned in 1949 that Ȍsten Undén considered naming Sohlman Cabinet Secretary, he wrote a letter to Swedish Prime Minister Tage Erlander advising him against the appointment, with the argument that Sohlman’s attitude towards the Soviet Union was “too uncritical”. Erik Boheman. På vakt: Kabinettssekreterare under andra världskriget [On Guard: Cabinet Secretary during the Second World War]. Stockholm: Norstedt, 1964. p. 25, cited in 987-5-88431-196-1_17.pdf (kunstkamera.ru)

[6] The National Archive and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, Maryland, USA. RG 84, [NND 947008], message via Air Pouch from Stockholm, December 7, 1956. Some Western ambassadors in Moscow reportedly had a very stern view of Sohlman, considering him essentially a “crypto communist”. https://www.svensktidskrift.se/arkiv100/2002/64%20Nils%20Andrén%3B%20Samtidshistoria%20i%20porträttformat.pdf

[7] See Olof Kronvall’s essay about Rolf Sohlman in Svenska Diplomatprofiler under 1900 talet [Profiles of Swedish diplomats during the 19th century], ed.: Gunnar Artéus and Leif Leifland. Visby: Probus főrlag HB, 2001. See also Kent Zetterberg. Östen Undéns Syn på det Internationella Systemet och den Internationella Politiken 1919–1965 [Östen Undén’s Attitude towards the International System and International Politics 1919–1965]; and Olof Kronvall. Östen Undén, Sovjetsyn och Sovjetpolitik 1945–1962 [Östen Undén, The Perception of the Soviet Union and Soviet Politics 1945–1962]; also, Mats Karlsson. Vår man i Moskva. En studie över den svenske ambassadören Rolf Sohlmans syn på Sovjetunionen och dess utrikespolitiska intentioner 1947–1950 [Our man in Moscow. A study of the Swedish Ambassador Rolf Sohlman's view of the Soviet Union and its foreign policy intentions 1947-1950]. Forskningprogrammet Sverige under kalla kriget. Arbetsrapport № 10. Stockholm, 1999.

[8] Zina Sohlman och hennes rysk släkt [Zina Sohlman and her Russian family]. ed. Staffan Sohlman, Stockholm: Sivart förlag AB, 2011. A Russian publication relates Zinaida Sohlman’s account of a Soviet intelligence agent’s approach to her brother, the artist A.A. Yarotsky, sometime before or around 1940. Her brother refused to cooperate. “After consulting with her husband, Zinaida herself met with this agent. She talked to Viktor Nikolaevich Timofeev (the adviser to the Soviet mission B.N. Yartsev, aka B.A. Rybkin, 1899-1947 - S. Berger) who introduced himself for more than two hours in his car. Having failed to get a promise of cooperation from Zinaida, "Timofeev" obtained from her a promise not to tell Madame Kollontay (the Soviet Ambassador in Stockholm, Alexandra Kollontay - S.Berger) about the meeting and their conversation. Zinaida agreed to make such a promise if he guaranteed that nothing would happen to her Soviet relatives (p. 86). Both kept their word. Zinaida told her brother the contents of the conversation and, upset, returned to the Moscow Hotel National, where she lived in 1940. The next day, she and her husband told the Swedish envoy to the USSR Assarsson about everything that had happened to Zinaida.” [Translation from the Russian] https://naukarus.com/russko-shvedskoe-rodstvo-v-usloviyah-revolyutsii-i-sovetskogo-totalitarizma-russkaya-semya-na-fone-epohi-vospominaniya-pi. {The link is currently not operational]

[9]”Tristast i går. Beredning kl. 16.30 om (Rolf) Sohlman och Åström. Torsten Nilsson, Rune Johansson + Belfrage + Danielsson + Vinge. Sohlman angavs som säkerhetsrisk.” Bo Theutenberg. Palme omvärderad? Dagbok från UD och mordet på Sveriges statsminister. [Palme reassessed? Diary from the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the murder of Sweden’s Prime Minister]. SILAC (Stockholm Institute of International Law Arbitration and Conciliation), 2023, p.33.

[10] The so called “Snackebanden” (Chat Tape). Wennerstrőm agreed to provide certain details to Swedish Security Police officials that would not be used against him at trial. Olof Frånstedt. Spionjägaren Del 1 [Spyhunter Part 1]. Västerås: Ica Bokförlag, 2014, pp. 108-09, and pp.167-68. It is not entirely clear what the Soviet contact person’s remark “from a higher level” referred to, if it indicated a source in Moscow or elsewhere. Usually, a source at a ‘higher level’ will mean a source with better local access to secret or important information.

[11] This included Western KGB agents like the British civil servant John Vassall. I would like to thank Anders Jallai for sharing important details and valuable insights into the official Swedish Security Police investigation of the time. The investigation took place in February 1963.

[12] See testimony of Anatolii Golitsyn; cited in Theutenberg, Vol.3, pp. 83-85. In 1961, KGB Major Anatolii Golitsyn (1926–2008) under the name "Ivan Klimov" was assigned to the Soviet embassy in Helsinki, Finland, as vice counsel and attaché. On December 15, 1961, he defected with his wife and daughter to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) via Helsinki. He was interviewed by James Jesus Angleton, CIA counter-intelligence director. Later he published several books. Domnika Cesianu was born in 1916. She was the daughter of Gheorghe Cesianu, a wealthy Romanian businessman. During the early1940s, she moved in the highest circles of Romanian societies, attending soirees and cocktail parties along with the top German Nazi leadership in Romania, such as the German Ambassador Manfred von Killinger, and his deputy Gerhard Steltzer. Steltzer and one of his colleagues, the German Police Attaché Gustav Richter, ended up in Soviet imprisonment. Richter spent time with Raoul Wallenberg in Lubyanka prison in Moscow in 1945. It is possible that Cesianu also knew Richter as part of her social circle in Romania.

[13] See Bo Theutenberg. Dagbok från UD, Vol. 5 (1986-88), 2021. Enclosure 4, citing a document in the [Vasily] Mitrokhin Archive at the Churchill Archive Center, Churchill College, UK; Folder K 2 – EUROPA, p. 62, point 326. Cesianu served in a “consular function” in Bucharest since the Swedish Mission in Romania was closed. Sohlman regularly traveled to Romania where he was also officially accredited. The entry states that Domnika Cesianu ”enjoyed Ambassador Sohlman’s confidence” and that she engaged in an "intimate relationship" with Sohlman, on the orders of the KGB.

Documentation in Swedish archives confirm that Sohlman and Domnika Cesianu were indeed personally acquainted. They stayed in contact at least until Sohlman’s departure from Moscow in late 1963. There is no independent confirmation for the alleged affair. Ambassador Sohlman was married since 1927 to Zinaida Sohlman. Domnica Cesianu married in 1938 but later divorced.

Sohlman was referenced under the code name “Solstickan” in the investigation of the Swedish Security Police, a play on words of the last name “Sohlman” and a brand name of Swedish matches actually called “Solstickan”. I would like to express my sincere thanks to Professor Theutenberg for generously sharing his insights, in particular about his research in the Mitrokhin archive.

[14] Memorandum signed by Swedish Security Police official Otto Danielsson, dated January 16, 1965. The document was part of a set of records provided to me by the Archive of the Swedish Security Police in a response to a request filed in 2022.

[15] In the early 1960s, officials like Cabinet Secretary Leif Belfrage explicitly approved Sohlman’s contact with his “academic friend” as a useful go-between in the highly sensitive discussions in the Raoul Wallenberg case and other top-secret issues, including incidents involving Swedish Soviet espionage scandals. See archive of the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Raoul Wallenberg dossier, P2 EU 1, memorandum signed by Leif Belfrage, February 7, 1961. Sohlman apparently claimed that his contact had a direct line to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. “Akademikern har enligt Sohlman nära nog omdelbar kontaktmöjlighet me Krustjev och en reaktion bör kunna erhållas mycket snabbt.” (According to Sohlman, the Academician has almost immediate access to Khrushchev and a reaction could be obtained very quickly). It does not appear that Sohlman or Belfrage were aware of the true name or identity of Sohlman’s contact.

[16] In March 1957, the Soviet government announced that years earlier it had uncovered a Swedish espionage network, supported by the U.S. and Great Britain. See Sohlman, March 8, 1957; and Sohlman to Undén March 12, 1957. In June 1952, Soviet fighter planes down two Swedish aircrafts over the Baltic Sea, resulting in the loss of an eight-men crew.

[17] Anders Sundelin. Diplomaten. [The Diplomat]. Stockholm: Svante Weyler Bokfőrlag: Stockholm, 2018. Chapters 91-92. About Sohlman’s discussions with Khrushchev Sundelin writes: “Det är ibland svårt att skilja sagesmannen från uppgiftslämnaren Var slutar russen? Var börjar Sohlman?” [It was sometimes difficult to distinguish the reporter from the source. Where did the Russian end? Where did Sohlman begin?]

[18] P2 Eu 1, Rolf Sohlman to Ȍsten Undén, February 16, 1961. “Trots allt kan man nämligen ej vara helt säker på att de i tid skulle erhålla de főr der nya lägets bedömande eforderliga uppgifterna genom sitt underrättelseväsende.”

[19] Ambassador Sohlman appeared to not be initially fully briefed about Fast’s background. Fast was sentenced to five years for attempted rape (våldakt). It appears that this charge was a pretext. See Svenske Sjőkaptenen utvisas från Sovjet [Swedish Sea Captain expelled from the Soviet Union]. Dagens Nyheter, March 9, 1960. Fast acknowledged of having been employed by Swedish Intelligence (IB). See Karin Bojs. Sjőmän var spioner [Sailors were spies]. Dagens Nyheter, September 8, 1990; and IB-Spion fängslades i Leningrad [IB agent imprisoned in Leningrad]. Dagens Nyheter, June 24, 1993. I am very grateful to Torsten Berglund and Lars Ekengren for providing this information.

The IB (Informationsbyrån or also known as “Inhämtning Birger”, after its director, the intelligence officer Birger Elmér) was formed only in 1965. In 1960, Captain Fast most likely was recruited by the maritime division of T-Kontoret, headed by Ove Lilienberg. See Thede Palm. Några studier till T-kontorets historia. Evabritta Wallberg, ed. Kungl. Samfundet för utgivande av handskrifter rörande Skandinaviens historia, Stockholm, 1999,

Aside from the “Fast affair”, Takhchianov and Sohlman discussed also “the Lybin case”. Sohlman, March 18, 1961. “Min akademiska bekantes tal om att han skulle kunda visa mig långa listor på Svenska agenter, verksamma även főr anglosachserna, samt hans aktualisering i samband Fast av fallet Lybin, vilket i allt fall tidigare sovjetisk agent, főrefaller numera mer begripligt.” Sohlman, March 18, 1961. Sohlman’s correspondence for the years 1949-1962 remains partly classified in Riksarkivet. I would like to express my sincere thanks to Monica Kleja for this information and for so generously sharing her time and expertise.

[20] Sohlman, December 26, 1963

[21] Петров Н.В. Кто руководил органами госбезопасности: 1941-1954 [Who was in charge of the State Security Services: 1941-1954] М. : Междунар. о-во «Мемориал»: Звенья, 2010. I would like to thank Dr. Nikita Petrov for generously sharing his expertise and for providing a photo of P.I. Takhchianov.

[22] Stanislav Lekarev, Hasan: chelovek-kinzhal [Hasan – the man with the dagger], Argumenty Nedeli, October 25-26, 2006. “Illegals” are Soviet agents operating abroad without diplomatic cover. I would like to extend my sincere thanks to Dr. Boris Volodarsky for making a copy of Lekarev’s article available to me and for taking the time to offer valuable insights and advice.

[23] Boris Volodarsky. Stalin's Agent. Oxford University Press, 2014. See also Unknown Agabekov. Intelligence and Security, Vol. 28, 2013, pp. 890-909.

[24] Volodarsky citing Pavel Sudoplatov and Anatoli Sudoplatov, with Jerrold L. Schlecter and Leona P. Schlecter. Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness – A Soviet Spymaster. London: Little, Brown and Company 1994, p.48. During the 1940s Lt. Gen. Sudoplatov headed the 4th NKVD/NKGB Directorate (Terrorist Acts and Diversion Services).

[25] See note 22. It is impossible to say if Lekarev’s account is accurate or an exaggeration or even an invention. Lekarev writes that Takhchianov was a skilled recruiter, a rare talent that led to special assignments, even in retirement. “Сейчас на пенсии, но все равно привлекается - уникальный спец, редкий опыт и мастерство вербовщика.” Lekarev, 2006, p.1.

[26] Sohlman to Stockholm, March 30, 1961. For the operational methods employed by KGB counterintelligence against foreign diplomats during the 1950s and 60s see Filip Kovacevic (2023) “An Ominous Talent”: Oleg Gribanov and KGB Counterintelligence, International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 36:3,785-815, https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2022.2095545 This included the KGB’s operation against the French Ambassador Maurice Dejean in 1956.

[27] Sohlman to Stockholm, April 2 and 4, 1961. Also, April 21, 1961. The article in question was by Soviet historian Lev Besymenskii. Himmler’s Secret Plan. International Affairs, no. 3, March 1961.

[28] Fredrik von Dardel’s diary, June 24, 1963. Sohlman based this information on the unconfirmed reports of Professor Nanna Svartz about her meeting with Professor Myasnikov in Moscow in January 1961. von Dardel eventually became frustrated with Sohlman’s efforts and referred to him as an “ineffective bastard”.

[29] The so-called Gromyko memorandum. Statement of the Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko on February 6, 1957, announcing that Raoul Wallenberg had allegedly died suddenly in his prison cell in Moscow ten years earlier, on July 17, 1947. https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2003/02/sou-200318-/

[30] Such discreet “signaling” was not entirely unusual. Just about a year before Gromyko’s statement, Ȍsten Undén and Sohlman had indicated to the Soviet side that they were ready to close the book on the Wallenberg case. Sohlman directly alluded to the possibility that “Beria and his consorts were to blame (for Wallenberg’s fate).” Undén made similar statements when he delivered a note on March 9, 1956, to the Soviet Ambassador in Stockholm K. Rodionov. In Soviet documentation Undén is quoted as saying that “the Swedish government would be satisfied with an answer that would hint at Wallenberg’s disappearance being an act of Beria.” See Ett Diplomatiskt Misslyckande: Fallet Raoul Wallenberg och den Svenska Utrikesledningen [A Diplomatic Failure: The case of Raoul Wallenberg and the Swedish Foreign Office]”. Statens offentliga utredningar (SOU) 2003:18 (in Swedish), p. 597.

[31] The Norwegian Ambassador in Moscow allegedly referred to Aleksandrov as Sohlman’s “confidante”. The memo provided no additional details. In his memo, Danielsson wonders if Aleksandrov could be the source for information about Raoul Wallenberg that Sohlman had recently shared with Wallenberg’s stepfather, Fredrik von Dardel. This does not appear to have been the case. Sohlman’s source was clearly Professor Nanna Svartz and the account she gave of her meetings with Professor Myasnikov in Moscow in 1961. See also note 1.

[32] The suspected Swedish military officer turned out to be Swedish Air Force Colonel Stig Wennerstrőm. See Sundelin. Diplomaten. Chapter 13; and Theutenberg. Dagbok från UD. Vol. 3, pp. 84-85 and pp. 99-100. According to Petrov, “Osa” refused to be fully recruited or to provide any written information. Osa/Getingen’s identity has never been fully confirmed. See https://susanneberger.substack.com/p/was-one-of-swedens-top-diplomats-a-soviet-asset-f25ca93a6839

[33] There is a small chance that the “G.V. Aleksandrov’ is a different person, but based on his CV, this appears to be unlikely. Anders Sundelin writes that V.A. Aleksandrov’s official title was “deputy director of the art workshops” at Byurobin. Sundelin. Diplomaten. Chapter 63.

[34] In 1921, the Council of Labor and Defense established the Foreigner Service Bureau (“Byurobin”), affiliated with the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs (a forerunner of GlavUpDK) “The bureau supplied diplomatic missions of various countries accredited in the RSFSR with accommodation, furniture, appliances and food.” In July 1947, Byurobin was transformed into the Administration for Service to the Diplomatic Corps under the USSR MFA (UpDK) https://medin.ru/en/o-medintsentre/istoriya-sozdaniya/

[35] Numerous witnesses have reported hearing about Raoul Wallenberg being held in this prison after his trail breaks off in Moscow’s Internal [Lubyanka] Prison in 1947. See independent consultant reports to the Swedish-Russian Working Group (1991-2001). Marvin Makinen and Ari Kaplan. Cell Occupancy Analysis of Korpus 2 of the Vladimir Prison, 2001; Susan Mesinai, Liquidatsia: The Question of Raoul Wallenberg’s Death or Disappearance in 1947, 2001. See also https://www.regeringen.se/rapporter/2004/01/raoul-wallenberg--report-of-the-swedish-russian-working-group/ For the precise dates of Aleksandrov’s imprisonment in Vladimir Prison see note 36.

[36] Sohlman, March 1, 1960. According to Aleksandrov’s prisoner card in Vladimir Prison, he had been arrested in 1947 on charges of treason committed by a civilian, as well as a lesser charge of sodomy (homosexuality). He was sentenced in 1948 to 20 years imprisonment. He was released in 1955. Aleksandrov arrived in Vladmir prison in 1949. I would like to extend my sincere thanks to Dr. Marvin Makinen, Ari Kaplan and Susan. E. Mesinai for providing details about V.A. Aleksandrovich imprisonment from his Vladimir prisoner registration card. My colleague Dr. Vadim Birstein explained the separate charges against Aleksandrov. They were espionage (treason committed by a civilian) Article 58-1 “a”; sodomy (homosexuality) Article 154 “a”; and speculation (decree of June 4, 1947).

[37] Sohlman, March 2, 1960

[38] Sundelin. Diplomaten, Chapter 63. Sundelin cites the Swedish Security Police interviews with Carl Ernst Fredrik Reinius in the Wennerstrőm case from January 27 and 28, 1964. Reinius worked at the Swedish Legation, Moscow from 1940-49. See also https://www.jallai.se/2012/07/sverker-astroms-hemlighet/.

[39] “During the Great Patriotic War, the bureau employees solved the most important tasks of ensuring the safety of foreign diplomats; by organizing their evacuation to Kuibyshev and controlling the safety of buildings for diplomatic missions in Moscow.” https://updk.ru/en/press-center/news/61991/

[40] As a homosexual, the Swedish Security Police considered Åström a high security risk. About the tactics used by the Soviet security services to compromise foreigners, including diplomats, in Kuibyshev in 1941-43 see Alf R. Jacobsen. Stalins svøpe: KGB, AP og kommunismens medløpere. [Stalin’s hostages: KGB, AP and Communist Followers]. Document Forlag, 2021

[41] Åström’s trip to Moscow supposedly came about through an invitation from Nikolai Semenov, Nobel Prize laureate in chemistry in 1956. See Svenska Dagbladet, September 6, 1959. Another article stated that he had been formally invited by the Swedish-Soviet Society and “associated organizations”. Svenska Dagbladet, September 17, 1959. Åström’s lecture had the title “Några aspekter på den svenska neutralitätspolitiken” [Some aspects of the Swedish neutrality policy]. Anders Sundelin provides a detailed review of the kind of lecture Åstrőm held at the time about Swedish-Soviet relations. Like Sohlman, he painted a positive picture of future mutual cooperation and conflict resolution. See Sundelin. Diplomaten. Chapter 91-921. Before Åstrőm left for Moscow, in early September 1959, Swedish Foreign Ministry officials had refused a request by Raoul Wallenberg’s parents to instruct Sverker Åstrőm to raise the question of Wallenberg’s disappearance during his trip. See Fredrik von Dardel’s diary (unpublished), September 3, 1959.

[42] “Det måste vara fruktansvärt att tvingas ta ställning till Åströms befordran, när polisen så enträget varnar. Men nu säger Olof Palme att Åström helst skulle vilja vara borta några år för att sedan komma tillbaka som kabinettssekreterare [emphasis added]. Då torde det lämpligaste vara att flytta Agda Rössel, som dessutom inte – fortfarande enligt Palme – orkar med ambassadörskapet i FN.” Theutenberg. Palme omvärderad. p.35

[43] Top Swedish Security Police officials indicated that they had no objections to Sohlman’s transfer to his new post in Denmark, even though Leif Belfrage apparently pointed out that as Ambassador Sohlman would still retain access to sensitive documentation. See note in Tage Erlander’s diary, September 4, 1963, cited in Theutenberg. Dagbok från UD. Vol 3, p. 88.

[44] Some very vague hints about this possibility are found in the Raoul Wallenberg case file in the Swedish Foreign Ministry archive. The file includes a report from Austrian Police authorities to Stockholm, dated December 6, 1954, based on the testimony of a man by the name of Marcel Rohan [alias Hellmann, alias Balcar]. The report outlined efforts to obtain economic intelligence from iron curtain countries via several groups of foreign agents, under the guidance of certain members of the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In the document this is referred to as the “Rolf Sohlman Plan”. According to the report, the respective groups were supposedly headed by Eastern and Central European exiles whose boss was a former Hungarian intelligence expert by the name of Karoly Palffy. Rohan’s testimony in the Wallenberg case was considered unreliable, but he clearly possessed knowledge about conditions in Eastern Europe and had connections to various intelligence groups. He did, for example, provide information about the capabilities of Eastern European defense industry, including the production of specific types of ball bearings, information that was of great importance to both Swedish industry and Western governments. However, Rohan’s statements about the “Rolf Sohlman plan” remain entirely unconfirmed.

The interview with Georg Thulin was conducted by General Carl Åhrman (FKE) on August 12, 1963. Thulin’s statement, as well as follow up comments regarding the need to censor the names of two or three Swedish double agents in the interview protocol, are referenced in the official report of the Wennerstrőm investigation (SOU 1964: 15); see Theutenberg, Vol.3, pp.100–02; 118–19. If any of these double agents were ever arrested by Soviet intelligence, their detention could have complicated the official Swedish handling of the Wallenberg case, for example. See Theutenberg. Dagbok fran UD, Vol. 3, pp. 108-9, cited in https://susanneberger.substack.com/p/was-one-of-swedens-top-diplomats-a-soviet-asset-f25ca93a6839.

[45] See application to Klas Friberg, Director of SÄPO, by Marie von Dardel-Dupuy and Louise von Dardel dated June 6, 2021.

[46] It is clear that other Swedish prisoners in Soviet imprisonment could have easily been mistaken for Raoul Wallenberg, for example. If researchers were unaware of these other individuals, it would not have been possible for them to properly evaluate witness testimonies in the Wallenberg case, the DC-3 investigation or the inquiry into disappeared Swedish ships and their crews. This would have resulted in a serious waste of research time and financial resources. The Swedish Working Group on the DC-3 (DC-3 Utredningen), was established in March 1991. It published its final report already in 1992. The Swedish-Russian Working Group on still outstanding questions in the Raoul Wallenberg Case was formally founded in June 1991 and was active for ten years, until 2001. It held about fifteen formal meetings, with additional separate discussions conducted by the Swedish and Russian sides throughout the years. It published two separate reports in 2001.The Swedish-Russian Working Group on disappeared ships and their crews was formed only in 1993. It held six official meetings between 1993 -1998. It was not formally disbanded until 2010, after a long period of inactivity. It never released a summary of its findings.